Taalaigul Usonova

Department of International Relations, Ala-Too International University, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Ailuna Shamurzaeva

Wroclaw University, The Lane Kirkland Program Fellow, Wroclaw, Poland

Introduction

Nowadays all the CA states continue transitioning into the human-centered model of governance where the comprehensive needs of societies must be satisfied, nevertheless, the achievements are to a greater extent ambiguous. According to the World Governance Indicators, the improvement of all the indices between 2000 and 2020 can be observed only in Uzbekistan, while this trend is not evident in the rest of the CA countries. Moreover, according to the estimations for 2020, the gap between countries in the quality of governance is formidable. For example, while by regulatory quality Kazakhstan outperformed half of the states covered by the study, Turkmenistan was among the outsiders standing in the lowest 10th percentile in the ranking. Is the distinction between the CA states determined by the initial country-specific internal aspects, for example, the quality of the public institutions or the quality of human capital? Or it is the result of the influence of the external agents, for example, the bilateral and multilateral good governance promotion assistance?

Various partners and donors are supporting inexperienced CA states in this transformation process. Since that early days, the EU has been one of the leading supportive partners and donors in the region. Over the period from 2002 to 2019 the EU is the third-largest donor in Central Asia after Japan and the United States. According to the Aid Atlas the total amount of development funding provided by the EU institutions, excluding the European Development Bank, achieved 607 mln USD.

Nevertheless, the substantial financial support of development programs in Central Asia opens discussions about the contribution of the initiatives endorsed by the EU institutions (EU). While the investigation of the impact of the EU on the political, social, and economic development of the Central Asian countries is an ambitious goal due to the multisectoral allocation of development funding, in this paper we set the modest objective to shed the light on the relationship between EU Aid and governance in five countries.

Research findings confirmed the positive impact of EU aid on good governance, moreover, compared with bilateral financial assistance from EU members the aid provided by the EU institutions was proved to be more effective (Dadasov, 2016). Accordingly, we hypothesize that EU good governance promotion aid facilitates the transition to the human-centered model of governance in Central Asia.

The paper is structured as follows. The first part overviews the development of EU- Central Asian Relations since 1991 and describes funding instruments, focal sectors, and EU good governance promotion approaches. The consecutive part unpacks the measurement of good governance which is followed by the synopsis of the current state of good governance in the Central Asian States. The final part explores the link between EU aid and good governance indicators.

Methodologically, the paper draws on document analysis of primary and secondary sources. The primary sources include statistical data retrieved from the Aid Atlas platform and the World Governance indicators dataset comprised by the World Bank for the period from 1996 to 2020. The secondary sources consist of a combination of academic publications, reports, and legal documents of the EU institutions.

1. EU good governance promotion in Central Asia

EU aid for good governance promotion

Traditionally, aid for good governance relied on the assumption of goodwill on behalf of recipient countries and the premise that the only obstacle to their implementing reforms was a lack of funds: this led in the early 2000s to the use of budget support as a preferred aid modality (Hayman, 2011). Accordingly, when the EU started promoting good governance EU officials relied on the assumption that EU aid would improve recipient countries’ governance. However, ineffective governance reforms in the recipient countries led to the introduction of the empowering citizenry approach presuming that interest in the effective provision of public goods would drive them to hold the governments accountable (Booth 2012). Thus with some exceptions of accommodating both “supply” government and “demand” civil society driven aid mainly EU aid designed separately sharing program ownership rarely with the exclusion of cases of a joint seminar or training sessions (Mungiu-Pippidi 2020).

The EU Commission has been broadening the definition of good governance and at the same time strengthened and specified the role of good governance since early 2000 as an important objective of EU development policy and EU external relations (Hackenesch 2016). For example, 2003 Communication on ‘Governance and Development’ states “Governance concerns the state’s ability to serve the citizens. Governance refers to the rules, processes, and behavior by which interests are articulated, resources are managed, and power is exercised in society. […]As the concepts of human rights, democratization and democracy, the rule of law, civil society, decentralized power sharing, and sound public financial management gain importance and relevance, a society develops into a more sophisticated political system and governance evolves into good governance” (European Commission 2003). The 2005 European Consensus on Development presents good governance as a precondition for sustainable and equitable development as well as for providing effective development assistance. Since the mid-2000s EU has put incremental emphasis on supporting governance reform through development policy which was facilitated by the international aid effectiveness agenda (Carbone 2010). In the 2006 Communication on ‘Governance in the European Consensus’ the Commission started speaking of democratic rather than good governance, indicating a quite broad understanding of the concept (European Commision 2006). The next development policy strategy, the ‘Agenda for Change’ stipulates that the EU should focus on its development cooperation in support of human rights, democracy, and other key elements of good governance; inclusive and sustainable growth for human development where it can have the greatest impact. In a word the “Agenda for Change” reinforced good governance as a priority (European Commision 2011). Moreover, based on a Communication, ’The Roots of Democracy and Sustainable Development: Europe’s engagement with Civil Society in external relations’ road maps for engaging with civil society in third countries have been developed (European Commission, The roots of democracy and sustainable development: Europe’s engagement with Civil Society in external relations 2012). Further in May 2014, the introduction of a ‘rights-based approach’ in the EU development policy led to “integrating human rights principles into EU operational activities for development, covering arrangements both at headquarters and in the field for the synchronization of human rights and development cooperation activities” and the DCI regulation for 2014–2020 required at least 15 percent of the funding for the DCI geographic programs (EUR 11.809 billion) should be spent on support for democracy, human rights, and good governance. . Working document 2021 ‘Applying the Human Rights Based Approach to international partnerships’ presents an updated Toolbox for placing rights-holders at the center of EU’s Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation (European Commission 2021).

Overview of EU-Central Asia relations

In 2021 the EU – Central Asian States diplomatic ties marked its 30th anniversary (“Central Asia | EEAS Website”, n.d.). Since the early days of Central Asian 5 State’s newly gained independence in 1991, the EU has been a supportive partner and leading donor in the region. In addition to the celebrations of the anniversary, on November 5, 2021, the first EU- Central Asia Economic Forum was held in Bishkek at the prime ministerial level which has reflected the commitments of the countries in green recovery, digitalization, and improving the business climate.

On the regional level development of EU – Central Asian relations evolved from the Technical Assistance for the Commonwealth of Independent States (TACIS) between 1991-2006 to the first Strategy on Central Asia 2007- 2019 which was expanded to the New Strategy was adopted in June 2019.

The pioneering projects and programs of the TACIS initiative worth billions of dollars supported the efforts of newly established CA states in implementing economic liberalization, free-market reforms, establishing rule of law, and democratization. This initiative paved the way for signing the Partnership and Cooperation Agreements (PCA) with five states however Turkmenistan’s is still pending ratification.

Due to the fact that the EU’s Eastern Neighborhood Partnership Instrument (ENPI) was launched to replace TACIS for the Eastern European states of the CIS, Brussels launched the first EU Central Asia Strategy in 2007. The strategy emphasized human rights, good governance, and democratization among other 6 priority areas: youth and education; economic cooperation, trade, and investment; strengthening energy and transport links; environmental protection, sustainability, water management; security and combatting common threats; intercultural dialogue.

By the end of the implementation deadline, the envisioned regional political dialogue at the Foreign Minister level and human rights dialogue was established, and the EU Rule of Law Initiative started. Despite the achievements, the overall strategy’s implementation success is evaluated as uneven in more substantive areas, such as the rule of law and human rights, the wider intraregional cooperation, and the EU-Central Asia energy sector cooperation (Emilbek Dzhuraev, Nargiza Muratalieva 2020). A New strategy on Central Asia prioritizes three strands: partnering with Central Asian states and societies for resilience (human rights and democracy, security, environmental challenges); partnering for prosperity (supporting economic diversification and private sector development, promoting intraregional trade and sustainable connectivity); supporting regional cooperation in Central Asia (“Basis for the EU – Central Asia Cooperation” 2022).

An updated strategy also paved the way for the enhancement of bilateral relations of CA states with the EU guiding the preparation of EU aid programming for the period of 2021-2027 and negotiation of new generation Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreements (ERCAs).

The EU aid instruments, focal sectors, and EU good governance promotion in Central Asia

Since 2007 EU assistance to the Central Asian States has been mainly financed via the geographic Development Cooperation Instrument (DCI). In the framework of the Regional Strategy Paper for Assistance to Central Asia for the 2007-2013 period, the EU pursued a more balanced dual track of bilateral and regional cooperation, with a regional approach for problems occurring across or involving all five countries, including water resource management, transport infrastructure, and antidrug trafficking initiatives, whilst following a bilateral, tailor-made approach for individual state issues (Bossuyt 2019). The priority areas of DCI assistance at the bilateral level between 2007-2013 were poverty reduction and increasing living standards; and good governance and economic reform (European Commission 2007).

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have been receiving a significant part of the DCI funding to support the sectoral budget to strengthen accountability and good governance. However, since 2014-2020 Kazakhstan and 2021-2027 multi-annual programming cycle Turkmenistan are no longer recipients of bilateral assistance via DCI reaching upper-middle income level.

In addition to DCI Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, received assistance via the “European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights” (EIDHR) which provides support to civil society through democracy and human rights-oriented projects, the Non-State and Local Authorities program (NSA-LA) which supports local participation in development and improve governance and the “Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace” (IcSP) which addresses development challenges. Furthermore, Central Asia benefits from an Instrument for a Nuclear Safety Co-operation Instrument (NSCI), primarily targeted at Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

On the regional level, the EU implements three Initiatives: the Rule of Law Initiative, the Education Initiative, and the Environment and Water Initiative. The Education Initiative brings together several existing cooperation programs: Tempus, Erasmus Mundus, Vocational Education and Training, and the Central Asia Research and Education Network. The Environment Initiative focuses on developing integrated water resource management, environmental protection, and climate change. Under the regional DCI header, the EU also provides support for border management, transport, and other sectors.

2. Unpacking Good Governance

Measurement of good Governance Indicators

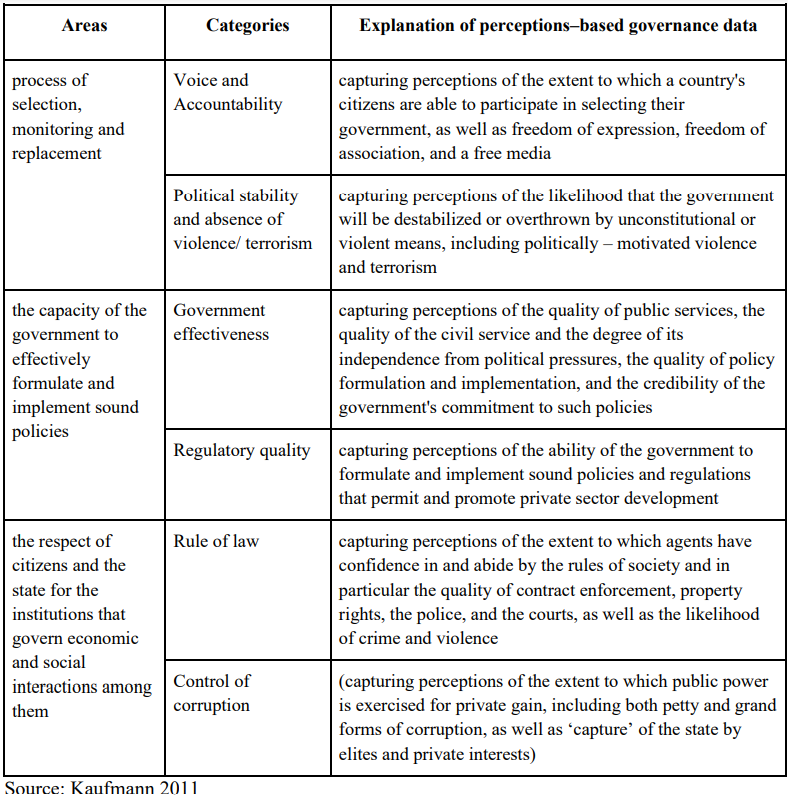

According to Kaufmann, a producer of the Worldwide Governance Indicators (Kaufmann, 2011) governance is defined as the traditions and institutions by which authority in a country is exercised. This includes the process by which governments are selected, monitored, and replaced; the capacity of government to effectively formulate and implement sound policies; and the respect of citizens and the state for the institutions that govern economic and social interactions among them. All three areas are assessed on the basis of input and perceptions–based governance data (see Table 1).

Systematic biases are considered to be the main limitation of the perception-based data, because respondents differ systematically in their perceptions of the same underlying reality and ideological orientation biases in the organization may provide a subjective assessment of governance. Despite the presence of subjective margins of error, the WGI is widely used in meaningful cross-country and over-time comparisons being the only available open-source of governance quality data today.

Synopsis of the current state of good governance in Central Asia

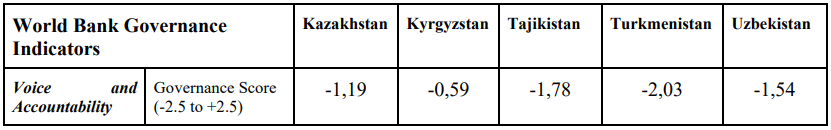

For evaluation of the governance in Central Asia, the World Governance Indicators generated by the World Bank were used. Table 2 provides synopsys of governance categories of CA states.

Several insights can be drawn from the Table 2.

1. The only parameter of good governance where the countries exhibited approximately similar and relatively high attainment was Political stability. This shows that authoritarian regimes employ the available resources to strengthen their power and exclude any attempts of the opposition/ other political actors to jeopardize the status quo. According to the report of the Freedom House, in 2020 all the Central Asian countries were recognized as states with Consolidated Authoritarian Regime (Freedom House, 2020).

2. The greatest disparity is seen in the rest of the categories. Due to the multifaceted nature of good governance progress in one of the edges spillovers the other aspects of good governance. Therefore, it is rather predictable that the same countries stand in leading (Kazakhstan) and lagging (Turkmenistan) positions throughout the governance indicators.

3. The enormous gap between countries in the quality of governance not only persisted but even widened. For example, the difference in the scores for the regulatory quality between the best and worst performers in 1996 was 1,48, however, in 2020 this gap approached 1,85. While Kazakhstan outperformed half of the states covered by the study in 2020, Turkmenistan was among the one percent of the countries in the ranking demonstrating a complete inability to formulate and implement sound public policies. Therefore, over the last 25 years, the divergence between the CA with respect to the development of good governance states exacerbated. The next part attempts to find out to what extent this divergence was subject to EU assistance.

3. The Link between EU Aid and Good Governance in Central Asia

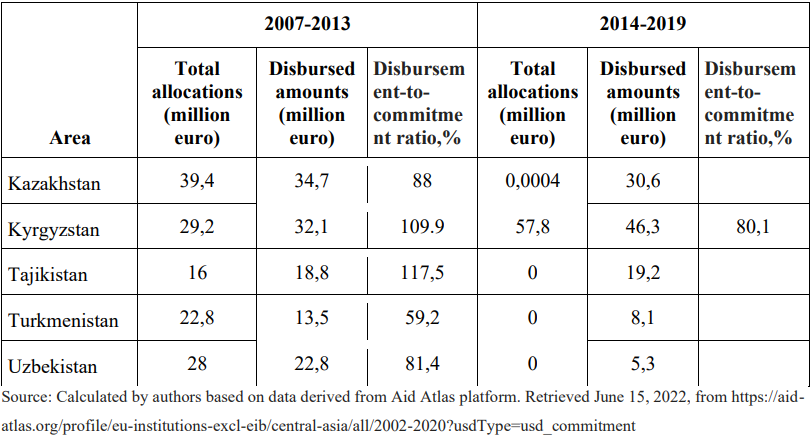

Analysis of EU Aid to Central Asia

The EU’s interest in the region was subject to changes, however, the total amount of aid committed to Central Asia in 2019 more than tripled relative to 2002. Moreover, it is noteworthy that over the given period the total commitment of EU Aid to Central Asia fluctuated from 106 mln USD to 218 mln USD, but in 2019 it reached an unprecedented 420 mln USD, which is more than twice as much as in the year earlier. The record outlay was owing to a considerable increase in support of Central Asian programs and projects in Tajikistan. The EU Aid allocated to Tajikistan in 2019 expanded from 10.3 to 93.5 mln USD (or by 9 times). In the Multi-annual Indicative Programme, 2021-2027 in Tajikistan three priority areas of the EU’s cooperation with the partner country were mentioned, among which the project ‘Natural resources management, efficiency, and resilience”. The profound sectoral analysis of EU allocation in Tajikistan revealed that more than 65 mln USD the EU will earmark to support completely new projects – more than 45 mln USD for implementation of Integrated Water resource management and 19 mln USD for Water Supply and Sanitation.

Approximately three fourth of the development assistance earmarked for Central Asia was provided through the DCI in 2012, while the remaining 25% was through the TACIS, DCI thematic programs, the EIDHR, and the Instrument for Stability. The amount of the development aid channeled to Kyrgyzstan mirrored that provided to Tajikistan in 2007-2012 (Norling&Cornell, 2016). Although DCI prevailed as a financial instrument, the good governance promotion in these countries was supported additionally through the EIDHR and NSA/LS (2.7. and 2 million USD respectively). However, neither of these instruments was applied to Uzbekistan, the development assistance there was channeled through DCI (38.6 million USD) and IBPP (2.2 million USD).

The consecutive multiannual indicative programme (MIP) adopted by the EU for the period 2014-2020 reinforced the DCI as the main financial instrument through which 174 million euros had to be allocated to Kyrgyzstan on a bilateral basis, supplemented by the thematic programs, for example, Rule of Law Programme which implementation would cost to the EU 26.5 million euro during 2014-2021 (EU-Kyrgyz Republic Relations, 2017).

The EU Aid allocation between countries has changed tremendously. Twenty years ago Tajikistan was the largest recipient of EU Aid absorbing 54 % of the total amount of development aid disbursed in the region, followed by Kyrgyzstan (13.7%). However, recently Tajikistan was overtaken by Kyrgyzstan, although both countries have almost the same ‘fraction of the pie’ now (22.2% and 20.4% respectively). Another pattern in funding allocation is the obvious inclination of the EU to support regional rather than national projects. While in 2003 23 % of EU Aid was dedicated to the implementation of the regional programs (South&Central Asia), in 2019 the share of regional projects in the total amount of disbursed aid increased to 35 % (Central Asia).

Due to the substantial heterogeneity of the countries by the state of economic development, the evaluation of the potential impact of EU aid on the economy should be complemented by the analysis of the relative indicators such as Aid-to-GDP and Aid per capita. Albeit the amount of EU Aid has increased substantially, in three out of five countries it remained negligible compared with GDP. EU Aid to GDP in Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan hasn’t witnessed significant changes. On the contrary, in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan share of the EU Aid has increased from 0.02% and 0.12% to 0.50% and 0.54% respectively. While EU Aid per capita in all Central Asian countries was close to zero in 2003, in the two largest recipients it demonstrated an even greater pace of change, achieving 6.5 USD in Kyrgyzstan and 4.6 USD in Tajikistan in 2019, although in the remaining countries it

remained below 1 USD.

Perhaps, these trends and patterns in EU Aid allocation can be explained by the relative openness of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to cooperation with the EU, or their economic disadvantageous position among other Central Asian countries. Aside from these factors, the political regime could contribute to the explanation of the range of EU Aid, probably authoritarian leaders of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan were reluctant to endorse the projects financed by the EU. The evidence supporting this assumption is the substantial increase in EU Aid to Uzbekistan after the change of President. If over the period from 2002 to 2015 EU Aid committed to Uzbekistan was 132 mln USD, for four subsequent years it achieved 102 mln USD.

Analysis of EU Aid by sectors: country level

Decomposition of EU Aid provided to Central Asia by sectors allows drawing several conclusions regarding the priorities of the EU in the region. First of all, from 2003-to 2005 the EU Aid unlikely can be referred to as development finance but rather as an “emergency aid” as a considerable fraction was provided in form of humanitarian and commodity aid. However, since 2016 the aid allocation has become to a greater extent balanced with significant financial resources dedicated to supporting economic and social development, which are the main pre-conditions for sustainable development of the region. For example, in 2019 EU allocated 22.61 % of the total amount of funding to support the projects related to the improvement of economic infrastructure, and 19.15 % – to support the private sector, albeit the largest fraction of Aid was provided to maintain the development of social infrastructure (43.81%).

Analysis of EU Aid for social infrastructure revealed the significant reallocation of funding between sectors. While funding of projects related to Government& Civil Society and Other Social infrastructure was curtailed substantially, projects in the following sectors: Water Supply&Sanitation, Education and Conflict, Peace and Security received greater support. Probably, the change in priorities reflects the commitment of the EU to contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals in the region, among which access to clean water and quality of education were highlighted. The financial support for projects in the area of Conflict, Peace, and Security is provided through regional initiatives, and directly to nation-states. The exclusive recipients of aid for conflict prevention are Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The sporadically exploding cross-border conflicts between two countries induced the EU to increase funding within this sector.

Nevertheless, the Government&Civil Society ranked second financially supported by the EU sector after Education, which is not surprising as the EU positions itself as a promoter of democracy and human rights protection within and beyond Europe. However, the amount of governance aid provided as well as its share of the total amount of development financing committed to Central Asia has decreased dramatically. The total amount of EU Aid allocated to the Government and Civil Society sector in Central Asia in 2003 peaked at 48 mln. USD, comprising 39,5 %, followed by a gradual decrease finally reaching 7.4% in 2019. This sector despite being prioritized in the regional program was pronounced as a focal sector only in the Kyrgyz Republic (namely, Rule of Law). According to the multi-annual indicative program for 2014-2020, the Kyrgyz Republic expected to be granted 37,72 million euros for the promotion of the Rule of Law, while in the remaining Central Asian countries the EU didn’t commit to contributing to the Government and Civil Society sector, however, the amount de facto disbursed over this period ranged from 5,3 to 30,6 million USD.

The instruments the EU employs to promote good governance in the region have changed considerably. Whereas in 2003-2005 the efforts of the EU were concentrated on the improvement of the quality of governance by enhancing the capacity of the public sector, later the focus shifted on the empowerment of civil society through the protection of human rights, promotion of democratic participation, and achievement of rule of law. This change in instruments is, in our opinion, justifiable, because without the demand for reforms in the public sector from the civil society, the efforts to improve public services will be always resource-consuming.

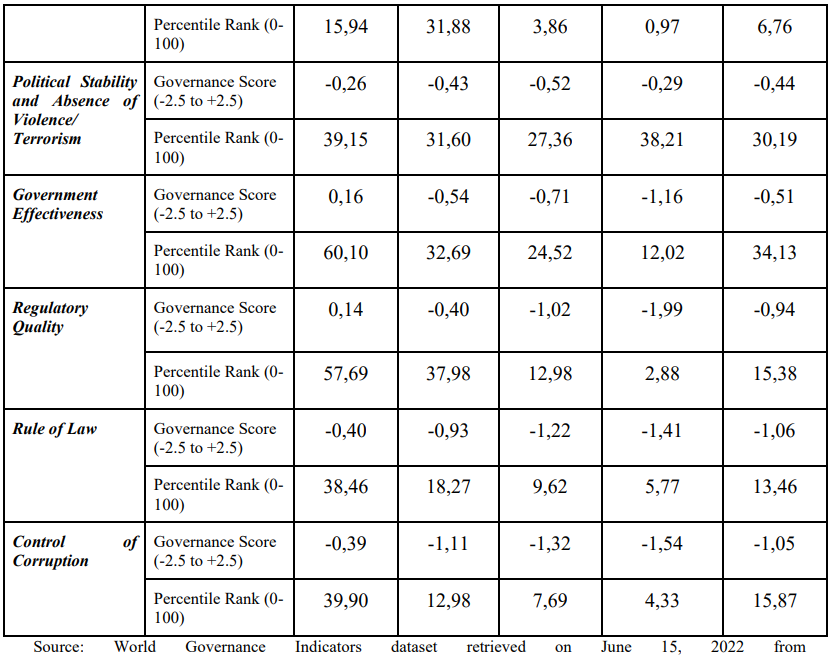

The analysis of the conditionality of the EU Aid provision was conducted by calculating the disbursement-to-commitment ratio for the projects related to the sector Government&Civil society, for the period from 2007 to 2019. Over the given period the highest absorption ratio was observed in Tajikistan, followed by Kyrgyzstan. The lowest disbursement-to-commitment ratio is attributed to Turkmenistan (59,2 %).

Despite the conformation to general policy in the region, the interests of the EU differ considerably, as it can be derived from the EU Aid allocation by sectors. Due to the discrepancies between amounts of governance aid committed and channeled to Central Asian countries, for the profound analysis of the EU assistance the latter one was considered.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan is one of the strongest economies in the region, with a still-authoritarian political regime. The distribution of development funding by sectors has changed tremendously in this country. In 2005-2006 less than 50% of EU Aid was occupied in the Social Infrastructure, whereas the lion’s share was allocated for multi-sector programs. However, in 2018-2019 around 90 % of EU Aid was dedicated to improving the social infrastructure, while the remaining funding was provided in the kind of humanitarian aid and for the implementation of multi-sector projects. The concentration of EU aid on several crucial sectors may be the result of different circumstances, for example, the local context, or change in EU’s strategic targets in the country-recipient. On the other hand, the focus on critical areas the EU aims to improve may be more efficient than implementing plenty of different programs scattered across sectors. Another insight, that can be drawn from the graph, is that recently the EU was not prone to support the real sector and economic infrastructure, although in 2007-2012 from 6% to 36% of EU Aid was used to support these sectors.

The EU Aid disbursed on Social infrastructure was distributed between the following sectors: Government and Civil Society, Education and Population Policies. Moreover, the share of EU Aid on good governance and democracy promotion was overwhelmingly high, in 2019 approximately two dollars of EU Aid out of three was dedicated to this sector, followed by Education (21.2 % of total EU Aid). While the structure of EU Aid to Social Infrastructure has not witnessed significant changes, the allocation of funding within the Government and Civil Society Sector has changed considerably. In 2005 more than half of EU Aid was provided to support the projects related to human rights protection in Kazakhstan, however, fourteen years later the share of this sector decreased to around 10%. At the same time, the Legal and Judicial Development sector was outside the list of focal sectors in 2005, but it became the main instrument of promotion of Good Governance in Kazakhstan, albeit initially, the EU expected to achieve this goal through financial support of the Public Sector Policy and Administrative Management.

Kyrgyzstan

The EU Aid to Kyrgyzstan, contrary to Kazakhstan, was to a greater extent fragmented and dispersed to varied sectors, however, the distribution of funding across the sectors altered. From 2005 to 2008 a significant portion of EU Aid flowed into Kyrgyzstan in the form of Commodity Aid (primarily Development Food Assistance) to support the development of Economic infrastructure. However, in the last four years, the priorities shifted to social and economic infrastructure. Kyrgyzstan also received Humanitarian Aid for three consecutive years from 2010 to 2012 which can be explained by the reaction of the EU to the political turbulence Kyrgyzstan experienced in 2010, and in that year the EU committed to providing financial support for the total amount of 3.7 million USD as an Emergency response.

The decomposition of EU Aid on Social Infrastructure reflects the country-specific instruments. The largest fraction of EU Aid in 2005 was allocated to support the projects related to the improvement of Governance, like in Kazakhstan. However, in 2015 and 2019 this sector was overtaken by Education, which absorbed more than a quarter of the total amount of EU Aid. The distribution of EU Aid within the sector of Government and Civil Society does not resemble the one observed in Kazakhstan. The share of sector Human rights which was modest in 2005, achieved 22% in 2019. The Public sector policy accommodated 86 % of EU Aid in 2005, however its share gradually decreased, reaching 3% in 2019. This decrease was compensated by the growth of EU Aid for Legal and judicial development, which became the major instrument for the promotion of Good Governance in Kyrgyzstan.

Tajikistan

The EU Aid allocation in Tajikistan was also dictated by country-specific factors. Contrary to the above-mentioned countries, Tajikistan for five years from 2003 to 2008 received humanitarian aid, the share of which in the total amount of aid disbursed fluctuated between 18% and 96%, however, in 2018 and 2019 it was less than 1 %. Over the period from 2009 to 2015 more than two-thirds of total aid was dedicated to the sectors Social Infrastructure and Production, later on, this list of principal sectors was extended by the Economic Infrastructure, which received from 25 to 38 % of EU Aid in 2016-2018.

Disaggregation of EU Aid on Social Infrastructure reveals more differences than commonalities with the countries analyzed so far. In contrast with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, more than a third of the total amount of aid was allocated to the sector labeled Other Social Infrastructure in 2005 and 2010. The government and Civil Society sector in Tajikistan, vice versa, received less than 15 % of total EU Aid. In 2019 about 16% of EU Aid was dedicated to Education, which is five times greater than in 2014.

The allocation of funding within the Government and Civil Society sector is peculiar as well. The first pattern which can be derived from the graph is the allocation of funding for Human Rights in 2005, however, the share of this sector decreased eventually reaching 19 % in 2019. Probably, it was dictated by a complicated social and political situation in Tajikistan after the long-lasting civil war. So the beginning of the new millennium Tajikistan reconstructed its political and economic system, therefore the EU couldn’t support programs aimed at enhancing the capacity of the government. Nevertheless, in 2010 and 2015 more than half of the funding was earmarked to improve Public Finance Management, while in 2019 it was surpassed by Democratic participation and civil society. Contrary to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, the EU was reluctant to support the projects related to the improvement of government efficiency and rule of law.

Turkmenistan

Over the period from 2006 to 2013 the share of Social Infrastructure in total EU Aid gradually increased reaching 86 %, but this trend reversed during the next four years. From 2015 to 2018 aside from Social Infracture, the EU aid was distributed between Economic Infrastructure, Production, and Multi-Sector programs. EU Aid to Social Infrastructure in Tajikistan was dedicated to Government & Civil Society and Education. The structure of aid for Government&Civil Society changed over time. If in 2005 the aid was allocated to the Public Sector Policy, however, in 2010 100% of aid was earmarked for Public finance management. In 2019 the greater support received programs in the Public sector policy, and the rest was allocated to Public Finance management.

Uzbekistan

Over the period from 2006 to 2015 more than 60 % of EU Aid was devoted to Social Infrastructure, however, over the next four years, the share of this sector halved. If in 2016-2017 the second sector with the highest ratio to total Aid was Multi-sector, over the two last years it was overtaken by Production. Aid for Social Infrastructure was distributed between Government and Education in 2006 and 2015. In 2019 neither of these sectors was financially supported but the Water Supply&Sanitation. The detailed analysis of aid within the Government&Civil Society sector demonstrates the same patterns that were observed in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. In 2005 and 2010 around 80% of aid was dedicated to the Public sector policy, however, in 2019 the share of this sector decreased to 12%. Apart from it, the other three sectors that occupied EU aid are Human rights, Public finance Management, and Ending violence against women and girls.

The main insights from the analysis:

1. The EU considerably contracted support of the reforms in the Government and Civil Society sector in all the Central Asian countries at the bilateral level, excluding Kyrgyzstan, but the Rule of Law referred to as the Regional Security priority at the Multiannual indicative regional program for 2014-2020 which deemed to be achieved through the EU-CA Rule of law Initiative.

2. Detailed analysis of the governance aid revealed that the EU tends to employ a similar set of good governance promotion instruments, there is a cross-country variance in the leading instruments which reflects the differentiation in priorities and interests of the EU in Central Asia. The efforts of the EU in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan are concentrated on the improvement of the Rule of Law and legal framework, promotion of effective policy decisionmaking, and protection of human rights. In contrast, in the remaining countries legal and judicial development is outside of the focus of the EU (especially after 2016), so governance assistance is provided to support initiatives in Public finance management and human rights protection.

3. Selection of good governance promotion instruments reflects the EU’s strategic priorities as well as can be bound by the ex-ante state of governance as well as the political regime in the Central Asian countries. The further analysis of the influence of the EU aid on governance in Central Asia will encompass only a limited set of sectors that absorbed the highest fraction of governance assistance.

The link between EU Aid and Good Governance in Central Asia (selected governance indicators)

The notable amount of finance directly channeled by the EU to the good governance promotion in the region raises the question about the contribution of EU Aid to good governance indicators. The analysis of the link between EU aid and selected governance indicators will embrace only the limited number of the main grant-receiving sectors, namely Legal and Judicial Development, Public Sector Policy, Human Rights, and Democratic Participation. Recognizing the possibility of lagged influence of the projects supported by the EU, in this analysis the relationship between the cumulative amount of aid, starting from 2003, and change in governance indicators will be considered. The data on the state of governance was retrieved from the World Governance Indicators database. Taking into account that the onset of the first strategy in Central Asia is dated 2007, the preceding year was used as a base year for this analysis.

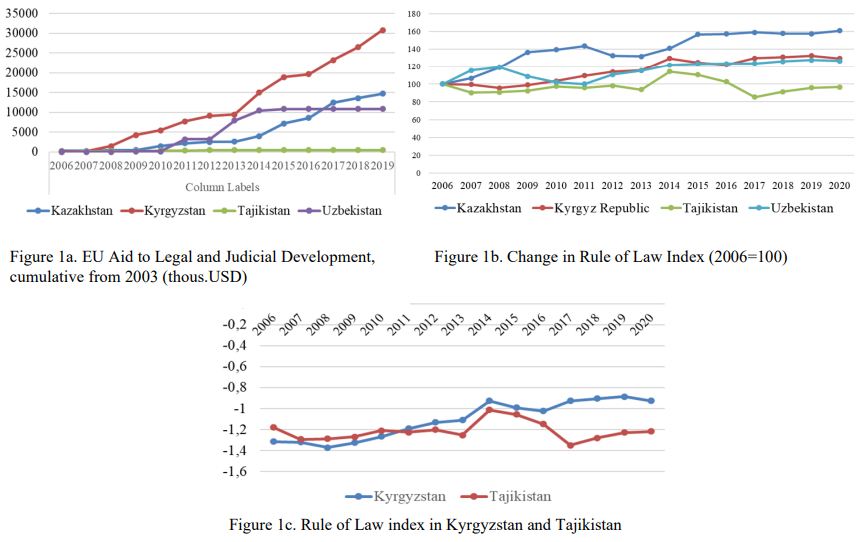

Rule of Law. As it was discussed earlier, there is an apparent distinction between countries in terms of the good governance promotion instruments. Kyrgyzstan is de jure the exclusive Central Asian country that receives EU aid earmarked for improvement of the Rule of Law, however, other countries, mainly Kazakhstan continued to gain grants which amounted to 12 mln USD over the period from 2014-2019 (see Figure 1). The EU’s support of the reforms in the legal and judicial areas of Tajikistan is almost negligible compared with Uzbekistan, where aid substantially increased in 2013-2014, but this positive trend halted completely afterward

Although Kyrgyzstan over the period from 2003 to 2019 received 2 times more assistance to promote the Rule of Law than Kazakhstan, 2,8 times more than Uzbekistan, and 68 times more than Tajikistan, the pace of change in the Rule of Law index is comparable with that of Uzbekistan. Among Central Asian countries, Kazakhstan succeeded in developing of a fair and inclusive legal framework. According to the WGI database, the Rule of Law index in Kazakhstan while never being positive, increased by 60 pp. relative to 2006. However, in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, the Rule of Law index followed the same trend, but in 2019 its change was two times lower than in Kazakhstan. The outsider in this group by the pace of change was Tajikistan, where it not only hasn’t improved but even deteriorated by 3.4 %.

In order to reveal the impact of EU aid on the legal environment the dynamic of the Rule of Law index was compared in the countries which can be referred to as the recipients of the greatest (Kyrgyzstan) and lowest (Tajikistan) amount of assistance. Figure 1.3. shows that in 2003 the difference in the Rule of Law index between the two countries was minimal. Moreover, Tajikistan outpaced its counterpart in 2006-2010. However, starting from 2017 gap has widened reaching 0.29 points in 2019. Therefore, we cannot unequivocally assert that EU aid contributes to the improvement of the Rule of Law in the region.

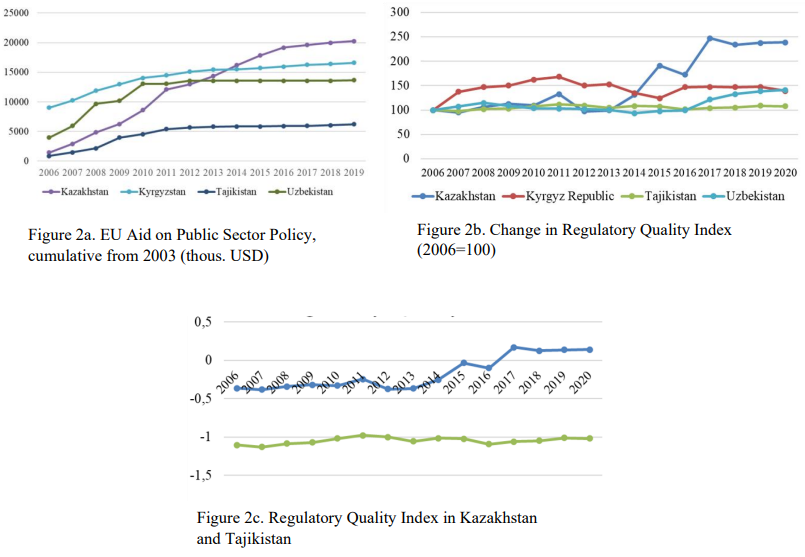

Regulatory Quality. During the period from 2007 to 2014, Public Sector policy was the leading instrument applied by the EU to promote good governance in Central Asia. Moreover, in 2007-2013 the greatest support this sector gained in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, but their positions were overtaken by Kazakhstan afterward (see Figure 2).

In our opinion, this sector concerns the development of effective and sound policies in the public sector, so the progress can be estimated by analyzing the corresponding Regulatory Quality Index. Change in this index relative to 2006 is represented in Figure 2.2. it is noteworthy that the period of the extensive contribution of the EU to the Public Sector Policy in Kyrgyzstan coincided with the greatest progress in the Regulatory Quality Index. However, starting from 2014, when Kazakhstan became the main recipient of aid in this line, the Regulatory Quality Index immediately jumped from -0.25 in 2014 to -0.03 the year after. Tajikistan, which received the lowest funding, has improved this index in 2019 only by 7% compared to 2006.

Finally, the quality of regulation in Kazakhstan (the largest recipient) and Tajikistan (the recipient of the least aid) was compared. According to Figure 2.3, the quality of public policy decision-making and implementation in Kazakhstan initially was better than in Tajikistan, and the gap between them was almost stable over the first seven years. However, generous funding Kazakhstan received in 2014-2017 lent impetus for the improvement of the public sector regulation, which resulted in progress in this index from -0.36 to 0.17, while in Tajikistan it hasn’t changed at all. Nevertheless, the success of Kazakhstan can be explained by other factors as well, for example, the assistance provided by other donors.

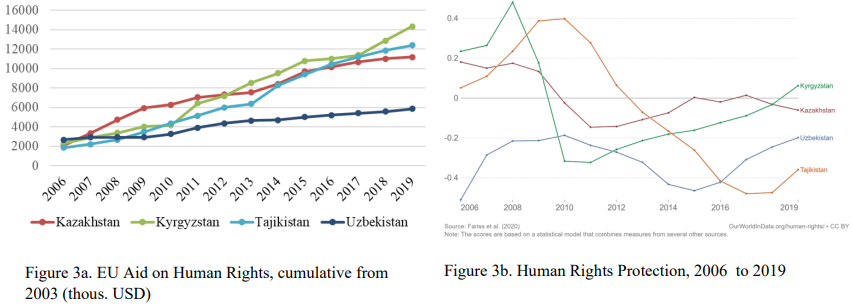

Human rights. Human rights protection initiatives are supported in all Central Asian countries, however, in 2006, all the countries received assistance approximately at the same rate (see Figure 3). However, after 2014 (after the adoption of the second EU Strategy in Central Asia) three of them – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, rapidly detached from Uzbekistan, which received 6 times less than other countries together over the period from 2003 to 2019. However, data on EU aid weakly, if not at all, correlates with the Human Rights Protection index, which measures the extent to which citizens’ physical integrity is protected from government killings, torture, political imprisonments, extrajudicial executions, mass killings, and disappearances (OurWorldinData, 2022).

This index is U-shaped for all the countries, with peaks and troughs achieved in different countries. In spite of an increase in aid channeled to human rights protection in Tajikistan, the state of human rights protection there deteriorated steadily up to 2018. In Kyrgyzstan, the fall in the Index of Human rights protection corresponded with the period of the presidency of K.Bakiev, however, after the second revolution an improvement in this index can be observed. Uzbekistan demonstrates the same pattern: the values of the Human Protection Index decreased starting from 2010 and reached the minimum in 2016. An improvement of this index is related to the rise to power of liberally oriented president Shavkat Mirziyoyev. So in general, we can conclude that there is no obvious relation between EU aid and human rights support.

Conclusion

The analysis of the relationship between EU governance aid and governance indicators has shown that the EU applies a variety of good governance promotion instruments, among which the primary one is the DCI. Cross-country analysis of the EU aid by sectors detected the differentiation in the instruments the EU opts for to foster quality of governance in Central Asia. The EU actively supports human rights protection initiatives in all Central Asian countries, but in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan since 2014 the EU was committed to promoting the Rule of Law, while in Tajikistan and Turkmenistan the EU prioritizes projects related to the improvement of transparency and accountability of Public Finance Sector.

The analysis of the impact of governance aid on selected main grant-receiving sectors: Legal and Judicial Development, Public Sector Policy, Human Rights, and Democratic Participation has shown that good governance can be affected by the interplay of external (international aid) and internal (political regime) factors. According to data, EU Aid can partially explain the gap between the largest and lowest assistance, however, other factors beyond the scope of this analysis could contribute to the best and poorest performance of the Central Asian countries, for example, the influence of other donors providing aid at the bilateral and multilateral levels, domestic policies (for example, aiming at the enhancement of the human capital capacity), etc.

Przypisy:

References

Aid Atlas | Visualise international development finance. (2022). Aid Atlas. Retrieved June 15, 2022,

from https://aid-atlas.org/profile/eu-institutions-excl-eib/central-asia/all/2002-

2020?usdType= usd_commitment

Basis for the EU – Central Asia Cooperation. 2022. The Diplomatic Service of the European Union.

https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/basis-eu-%E2%80%93-central-asia-cooperation_en.

Bastian Herre and Max Roser (2016) – „Human Rights”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org.

Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/human-rights’ [Online Resource]

Booth, D. 2012. “Synthesis Report – Development as a Collective Action Problem: Addressing the

Real Challenges of African Governance, Africa Power and Politics Programme.”

Bossuyt, Fabienne. 2019. “The EU’s and China’s development assistance towards Central Asia: low

versus contested impact.” Eurasian Geography and Economics.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15387216.2019.1581635.

Carbone, M. 2010. “The European Union, Good Governance and Aid Co-ordination.” Third World

Quarterly 31 (1): 13–29.

Central Asia | EEAS Website.n.d. EEAS. Accessed July 23, 2022.

https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/410470_ar.

Dadasov, R. (2017). European aid and governance: Does the source matter? The European Journal

of Development Research, 29(2), 269–288. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2016.16

Emilbek Dzhuraev, Nargiza Muratalieva. 2020. “THE EU STRATEGY ON CENTRAL ASIA,” To

the successful implementation of the new Strategy. FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG.

https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/bischkek/16168.pdf.

EU-Central Asia relations, factsheet | EEAS Website. (2017). EU External Action.

https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/34927_en

EU-Kyrgyz Republic relations, factsheet | EEAS Website. (2017). EU External Action. Retrieved July

26, 2022, from https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2.factsheet_on_eukyrgyz_republic_relations.nov_.18.pdf

European Commision. 2003. “Governance and Development.”

European Commision. 2006.

European Commision. 2011. “Increasing the impact of EU Development Policy: an Agenda for

Change.” Brussels.

European Commision. 2012. “The roots of democracy and sustainable development: Europe’s

engagement with Civil Society in external relations .”

European Commission. 2007. “European Community Regional Strategy Paper for Assistance to

Central Asia for the Period 2007–13.”

European Commission. 2021. “Applying the Human Rights Based Approach to international

partnerships.” Brussels.

Freedom House. (2020). Explore the Map. Democracy Status. Retrieved August 24, 2022, from

https://freedomhouse.org/explore-the-map?type=nit&year=2022

Hackenesch, Dr. Christine. 2016. “Good Governance in EU External Relations:What role for

development policy in a changing international context?” Belgium.

Hayman, R. 2011. “Budget Support and Democracy: A Twist in the Conditionality Tale. , 32(4),.”

Third World Quarterly 32 (4): 673–688. doi:doi:10.1080/01436597.2011.566998

Human Rights. OurWorldinData. Retrieved on July 29, 22 from :

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/human-rightsprotection?tab=chart&time=2006..latest&country=KAZ~KGZ~UZB~TJK

Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, Massimo Mastruzzi. 2011. “The Worldwide Governance Indicators:

Methodology and Analytical Issues.” Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 3: 220- 246.

Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. 2020. Europe’s Burden Promoting Good Governance across Borders.

Cambridge University Press. www.cambridge.org/9781108472425.

Norling, N., & Cornell, S. (2016). The role of the European Union in democracy-building in Central

Asia. IDEA. Retrieved July 26, 2022, from https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/roleeuropean-union-democracy-building-central-asia-and-south-caucasus

Peyrouse, S., J. Boonstra, and M. Laruelle. 2012. “Security and Development in Central Asia. The

EU compared to China and Russia..” EUCAM Working Paper no. 11. doi:10.1094/PDIS11-

11-0999-PDN.

Sharshenova, Aizhan. 2015. “European Union Democracy Promotion in Central Asia Implementation

in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.” The University of Leeds School of Politics and International

Studies.

Transactions from the EU Institutions to Central Asia (by recipients), 2002-2019. Retrieved on June

15, 2022 from: https://aid-atlas.org/profile/eu-institutions-excl-eib/central-asia/ governmentcivil-society/2002-2019?usdType=usd_commitment

czytaj więcej

Paweł Behrendt w rozmowie z cyklu Zoom na Świat „Indo-Pacyfik. Czy będzie wojna?”

Serdecznie zapraszamy do wysłuchania rozmowy z cyklu Zoom na Świat "Indo-Pacyfik. Czy będzie wojna?", w której wziął udział analityk Instytutu Boyma, Paweł Behrendt.

Temples, Hackers, and Leaks: The Thai-Cambodian Crisis in the Age of Information Warfare

Thailand and Cambodia are caught up in a heated border dispute over an ancient temple that dates back to the 11th century. This isn’t just about land — it’s about the heritage of colonialism, national pride, and tensions between two powerful political dynasties.

Andżelika SerwatkaTydzień w Azji: Kazachstan wybrał stabilizację

Wybory parlamentarne w Kazachstanie, które odbyły się 10 stycznia, nie przyniosły istotnych zmian politycznych. Brak protestów społecznych, podobnych do Białorusi czy Rosji może wskazywać, że Kazachowie nie oczekują zmian, a przede wszystkim aktywnej polityki społecznej, kontynuacji rozwoju gospodarczego oraz stabilności rządów.

Jerzy OlędzkiPolish-Macanese Artist Duo Presents New Works in Lisbon

Artist couple Marta Stanisława Sala (Poland) and Cheong Kin Man (Macau) will present their latest works in the exhibition “The Wondersome and Peculiar Voyages of Cheong Kin Man, Marta Stanisława Sala and Deborah Uhde”, on view at the Macau Museum of the Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre (CCCM) in Lisbon, from 5 June to 17 August 2025.

Tydzień w Azji #206: Chinom grozi exodus miliarderów

Przegląd Tygodnia w Azji to zbiór najważniejszych informacji ze świata polityki i gospodarki państw azjatyckich mijającego tygodnia, tworzony przez analityków Instytutu Boyma we współpracy z Polskim Towarzystwem Wspierania Przedsiębiorczości.

Tydzień w Azji #40: GoJek wchodzi do rządu

Przegląd Tygodnia w Azji to zbiór najważniejszych informacji ze świata polityki i gospodarki państw azjatyckich mijającego tygodnia, tworzony przez analityków Instytutu Boyma we współpracy z Polskim Towarzystwem Wspierania Przedsiębiorczości.

Oferta stażu w Instytucie Boyma

Poszukujemy pasjonata spraw azjatyckich z wysokimi kompetencjami w świecie technologii, który czuje się komfortowo w cyfrowym środowisku i potrafi doprowadzać sprawy do końca.

Zespół Instytutu BoymaTydzień w Azji #238: Węgrzy chcą na nowo sporządzić mapę gazową Europy

Przegląd Tygodnia w Azji to zbiór najważniejszych informacji ze świata polityki i gospodarki państw azjatyckich mijającego tygodnia, tworzony przez analityków Instytutu Boyma we współpracy z Polskim Towarzystwem Wspierania Przedsiębiorczości.

RP: Indie – o czym warto pamiętać przygotowując pierwsze spotkanie biznesowe

W fazie dynamicznego indyjskiego odbicia po zeszłorocznym pandemicznym załamaniu, wielu eksporterów spogląda ponownie na Subkontynent. Tym, którzy stawiają tam pierwsze kroki, przypominamy kilka prostych zasad, o których warto pamiętać w biznesie.

Krzysztof ZalewskiPrzegląd Tygodnia w Azji to zbiór najważniejszych informacji ze świata polityki i gospodarki państw azjatyckich mijającego tygodnia, tworzony przez analityków Instytutu Boyma we współpracy z Polskim Towarzystwem Wspierania Przedsiębiorczości.

Forbes: Klan nietykalnych, czyli ciemna strona południowokoreańskich czeboli

Szefowie Samsunga nie zawsze grali czysto. Zarówno syn jak i wnuk założyciela słynnego czebola mają na swoich kontach bogatą historię skandali gospodarczo-korupcyjnych, które za każdym razem mocno wstrząsały opinią publiczną.

Andrzej PieniakTydzień w Azji #328: Jest nowa nadzieja w boju o metale ziem rzadkich. Uda się wygrać z Chińczykami?

Przegląd Tygodnia w Azji to zbiór najważniejszych informacji ze świata polityki i gospodarki państw azjatyckich mijającego tygodnia, tworzony przez analityków Instytutu Boyma we współpracy z Polskim Towarzystwem Wspierania Przedsiębiorczości.

Azjatech #218: Awatary wspierają nauczanie w małych szkołach w Japonii

Azjatech to cotygodniowy przegląd najważniejszych informacji o innowacjach i technologii w krajach Azji, tworzony przez zespół analityków Instytutu Boyma we współpracy z Polskim Towarzystwem Wspierania Przedsiębiorczości.

Jeśli pandemiczne ograniczenia mogą być symbolem samoizolacji Chin, to ostra retoryka w polityce zagranicznej świadczy o coraz mniej skrywanych agresywnych planach wobec sąsiedztwa.

Zespół Instytutu BoymaList z Instytutu Adama w Jerozolimie

Ten list jest częścią naszej serii Głosy z Azji. Dzielimy naszą platformę z dr Uki Maroshek-Klarman, która pełni funkcję Dyrektora Wykonawczego w Instytucie Adama ds. Demokracji i Pokoju w Jerozolimie, w Izraelu.

Uki Maroshek-KlarmanAzjatech #12: Przegrzanie chińskiego sektora technologicznego

Azjatech to cotygodniowy przegląd najważniejszych informacji o innowacjach i technologii w krajach Azji, tworzony przez zespół analityków Instytutu Boyma we współpracy z Polskim Towarzystwem Wspierania Przedsiębiorczości.

Ciasteczko z wróżbą o chińskim PKB 2023

Najsłynniejszy cel gospodarczy ogłaszany przez władze CHRL – wzrost chińskiego PKB - ma wynieść ok. 5% w 2023 r.

Adrian ZwolińskiAzjatech #31: Nie tylko Huawei. Rośnie kolejny chiński gigant elektroniczny

Azjatech to cotygodniowy przegląd najważniejszych informacji o innowacjach i technologii w krajach Azji, tworzony przez zespół analityków Instytutu Boyma we współpracy z Polskim Towarzystwem Wspierania Przedsiębiorczości.

Zrobieni w dżucze. Recenzja książki „North Korea’s juche myth” B.R. Myersa

Nowa książka B.R. Myersa reklamowana była pochlebną recenzją Christophera Hitchensa. Podobnie, jak słynny neoateista Myers znany jest ze swojego ostrego języka, stanowczych i kontrowersyjnych tez, błyskotliwych spostrzeżeń oraz świetnego pióra. Wszystko to w najlepszej odsłonie ukazuje najnowsza książka badacza Korei Północnej: North Korea’s juche myth. Myers rozpoczyna swoją pracę, od krytyki innych ekspertów tematu. Zarzuca […]

Roman HusarskiAdrian Zwoliński w Telewizji wPolsce o pułapce zadłużenia w kontekście Chin

Gościem programu Aleksandry Rybińskiej był ekspert Instytutu Boyma Adrian Zwoliński. Analityk opowiadał o zagadnieniu popularnie określanym "pułapką zadłużenia" w odniesieniu do pożyczek udzielanych przez Chińską Republikę Ludową

Adrian ZwolińskiTydzień w Azji #149: Litwa solą w oku Chin

Przegląd Tygodnia w Azji to zbiór najważniejszych informacji ze świata polityki i gospodarki państw azjatyckich mijającego tygodnia, tworzony przez analityków Instytutu Boyma we współpracy z Polskim Towarzystwem Wspierania Przedsiębiorczości.

Azjatech #56: Japonia uchwala ustawę o „super-miastach”

Azjatech to cotygodniowy przegląd najważniejszych informacji o innowacjach i technologii w krajach Azji, tworzony przez zespół analityków Instytutu Boyma we współpracy z Polskim Towarzystwem Wspierania Przedsiębiorczości.

Tydzień w Azji: 17+1 w dobie koronawirusa: wnioski z webinaru China-CEEC Think Tank Network

Podczas epidemii COVID-19 Chińczycy nie rezygnują z koordynowania działań stworzonego przez siebie formatu współpracy 17+1. Przedmiotem rozmów, ze względu na trudną sytuację epidemiologiczną i gospodarczą, stały się polityki i rozwiązania wprowadzone przez poszczególne państwa w tym zakresie.

Patrycja PendrakowskaAzjatech #228: Drony na ratunek ofiarom trzęsienia ziemi

Azjatech to cotygodniowy przegląd najważniejszych informacji o innowacjach i technologii w krajach Azji, tworzony przez zespół analityków Instytutu Boyma we współpracy z Polskim Towarzystwem Wspierania Przedsiębiorczości.