After the darkness of the Cultural Revolution, the times of the Chinese transformation had come. In 1978, Deng Xiaoping realised the need to educate a new generation of leaders: people proficient in science, management and politics. Generous programmes were created that aimed at attracting back to China fresh graduates of foreign universities, young experts, entrepreneurs and professionals. Deng’s decision resulted in an ever-increasing number of both Chinese students going abroad and highly educated specialists returning home. Many returnees, however, experience cultural shock and question their own identity.

Introduction

Migrations is an extremely hot topic nowadays. Especially if one talks about it in the context of the world’s most populous nation as China is. The Middle Kingdom has been no stranger to large-scale migration, both historically and in modern times. The Lunar New Year’s trips, described by some scholars and international media as “wandering of the peoples” and “the largest annual human migration”, form the most consistent of the mass travel phenomena in the country. But arguably the most impactful type of migration of the 20th and 21st century Chinese is the one of well-educated expatriates.

Haigui (海归 hǎiguī), in a literal translation from Mandarin, means “returning from across the sea”. This term refers to a person who came back to the country after having studied or worked abroad. In English, such people are called “sea turtles”, as that is the meaning of the homonym word haigui (海龟 hǎiguī). In addition, sea turtles, like haigui, take long journeys across the sea. According to the data, in the last 40 years, more than 6.5 million Chinese have returned to their homeland (China Daily, 2020). They are often people equipped with rare knowledge and skills acquired abroad, who speak foreign languages and have developed intercultural communication skills. In the coming decades, haigui could make a major contribution to China’s development and international empowerment.

In the first part of this work, I attempt to summarize the history of China’s policies towards haigui, focusing mainly on the period after Deng Xiaoping’s reforms of 1978. I identify the reasons for expatriates’ decisions to return to the country and the tools that the state employs to encourage them to do so. I outline the position haigui occupy in the society, the paths of assimilation and their ways to cope following return. Finally, I note their contribution to the modernisation of the state and venture to determine the future prospects that might await them.

While writing this paper, I relied on articles examining transformation of China’s policy towards haigui. I have analyzed government reports on the numbers of returnees and state programmes addressed to them. I have also reviewed news media stories that included accounts of people returning to their homeland. They all shared their experiences: both successes and failures, difficulties and needs.

Brain deficit and brain drain

In 1966, the Cultural Revolution had begun. The campaign started with the aim to get rid of Mao Zedong’s political rivals, as well as to implement his ideology. Part of the fight against the opposition was persecution of intellectuals, who were often sent to the countryside, where they suffered years of re-education. Professors, scholars and experts were forced to self-criticize. They found themselves in the group of the “Stinking old ninth” (臭老九 chòu lǎo jiǔ), which was a scornful term used on victimized social groups. The following ten years of the revolution destroyed the rich scientific and cultural heritage of the country.

In the 1960s, as part of the strategy aimed at keeping up with the West, Chinese students were sent to study science and management in the Soviet Union and other countries of the Eastern Bloc. It was only in the two following decades, at the beginning of economic reforms and policies of opening-up to the world, when Deng Xiaoping highlighted the need to catch up with Western countries in the fields of information, new technologies, international policy, etc. Thus he began sending three thousand students a year (Scidev Net, 2008) to foreign universities. After having returned to the country, they were to implement foreign solutions in order to strengthen China’s position on the international stage. In the early stages of the reforms, China could not provide sufficient funding to finance foreign education, and it did not have much to offer to returning graduates. Foreign universities, on the other hand, not only offered them attractive scholarships, but also wider career opportunities. As a result, many of them never returned to China.

To encourage expatriates to return from abroad, Deng Xiaoping, as a part of the so-called Open Door Policy, liberalized the approach towards haigui. He declared openness to all, regardless of political views that they held before the Tiananmen square events, and offered many facilitations, e.g. possibility of renewing their passports, as well as choosing a place to live and work, bringing their families along (Full Text of Jiang Zemin’s Report at 14th Party Congress, 2011).

In the 1990s, president Jiang Zemin continued to encourage students to come back and participate in the process of modernization of the country. At the 14th Party Congress, he spoke about the need to create better business conditions and more transparent regulations in order to attract as many entrepreneurs, professionals and intellectuals as possible from abroad (Beijing Review, 2011). At the third plenum of the 14th Party Congress, the slogan was created: “Support overseas study, encourage people to return, and give people the freedom to come and go (来去自由 láiqù zìyóu).”

President Hu Jintao, on the other hand, said that China should devote more economic resources to three key links of human capital: training, recruitment and talent use. It was attracting and effectively exploiting the potential of the greatest Chinese talents from abroad that the state focused on their efforts in the years that were to come.

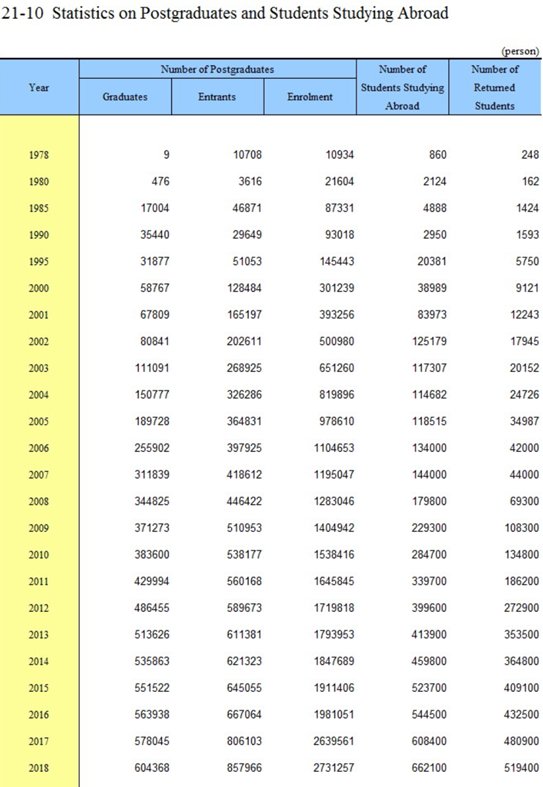

Incentives and rewards for haigui

Supporting foreign education became one of the country’s priorities. To this end, the whole national system of managing the affairs of students at foreign universities has been built. This has been implemented in higher education institutions and research centres, at both national and local level. The system relies on three forms of financing: state funding, employer funding and self-financing. As a result of these efforts, the total number of students studying abroad between 1978 and 2003 amounted to 700,200 individuals at institutions of higher learning in 108 countries. Almost half of them studied in Europe (Ministry of Education of The People’s Republic of China, 2009).

At the same time, as part of the country’s modernization strategy, serious attempts were made to attract graduates, young scientists and entrepreneurs. As part of its approach towards Chinese people from abroad, the government created a number of programmes and regulations designed to encourage them to settle in China, making it easier for overseas residents to return to the country or cooperate from abroad. In the 1980s, efforts were made to attract young scientists and doctors in particular, by creating preferential conditions for work and self-development. In the 1990s, a research fund for about 1,000 returning students was set up. Some cities, such as Shenzhen, Shanghai and Fujian have created favourable legal environments, as well as privileged working and housing conditions. Soon, Deng Xiaoping announced that China would also welcome those students who had expressed their opposition to the government during the Tiananmen era, provided that they did not take further political action. Regulations were created allowing returning students and academics to live with their families and work anywhere, effectively lifting in their case the restrictions imposed by the hukou (household registration) system.

In 1993, the Party coined the slogan: “Support the overseas studies, encourage Returnees to China, grant the freedom to come and go”. Since then, many large, high-budget projects have been created. Among them was the “Program for Training Talents toward the 21st Century”, implemented by the Ministry of Education, which attracted more than 9,000 outstanding teachers. In turn, the “One Hundred Talents”’ programme set itself the goal of attracting 100 natural sciences researchers, and in the following years this goal was exceeded fourfold. In 1996, the Chunhui project was launched to provide financial support to those who came for short-term visits, mainly doctors. More than 8,000 such visits have been funded since then and the programme is still active. Jiang Zemin initiated the “985 Plan”, which allocated billions of yuans for the development of world-class Chinese universities, spending most of the budget on two institutions: the Beijing University and the Tsinghua University. Another ongoing initiative is the “Changjiang Scholar Incentive Program” that funds year-long visits to China for researchers in the areas of strategic importance for the country.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the main focus of the policies towards returnees has been on law reform and the creation of haigui-friendly regulations. New incubator rules have been created, allowing work in the selected fields of study with the possibility of retaining existing citizenship and facilitating free arrival and departure for foreign investors. In 2005, the government focused its policy on attracting “the greatest foreign talent”. Many institutions are involved in the work on the relevant regulations, e.g. the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People’s Bank of China and the Chinese Academy of Science (Ministry of Education of The People’s Republic of China, 2009).

Various actions have been taken, which, in conjunction with the above mentioned programmes, aim to improve support for talent development and encourage Chinese scholars to return. Firstly, systemic reforms have been made and the numbers of students sent abroad increased. Secondly, innovations have been introduced to increase flexibility. In this regard, the liuxue.net website, which serves as a platform of communication for foreign students and employers, has been improved; the “Expressway Mechanism”, which connects students returning from abroad with universities in China has been strengthened. Thirdly, the promotion of flexible programmes has been introduced, allowing cooperation in academic exchanges, joint research and projects with those who have decided to stay abroad. The goal is to develop a friendly legal environment for entrepreneurship. The Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Public Security have announced the possibility of a 5-year stay with a multi-entry visa for foreign employees of universities and research institutions, as well as the option of permanent residence for those with outstanding talent, if they offered to serve the state. Moreover, learning conditions have been created for children of those returning from abroad and opportunities for their partners to work. Finally, the government has decided to link multilateral cooperation with the development of China’s western regions and attract more haigui there (Ministry of Education of The People’s Republic of China, 2009).

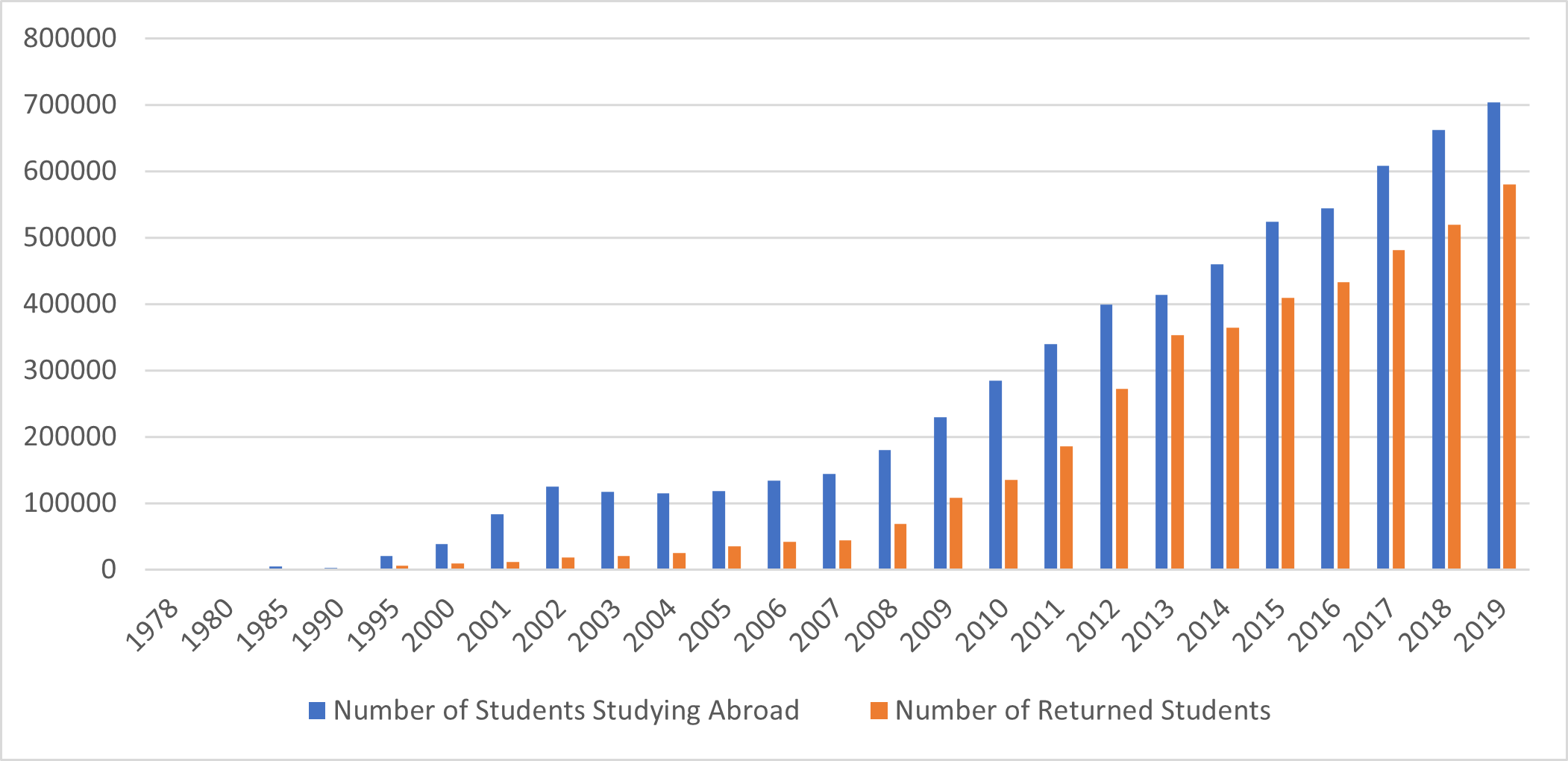

The results of all these activities are clearly visible as the statistics show that the number of people returning from studies abroad is constantly increasing. In 2017, the Ministry of Education of the PRC reported (Ministry of Education of The People’s Republic of China, 2018) that there was a steady increase in the number of both students studying abroad and those returning after having completed their education. The record number of more than 608,000 students had gone to study overseas that year, which gave China the world’s first position in this category. More than 480,000 of them have decided to return.

The United States and Western Europe remain the most popular study destinations (Ministry of Education of The People’s Republic of China, 2018), but in recent years, with the growing role of the Belt and Road Initiative, other countries have also gained popularity. In 2017, a total of more than 66,000 students studied in 37 states of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which is almost a 16% increase from the previous year. A vast majority, almost 89%, paid for their studies, and the number of people studying under programmes funded by local government institutions and employers increased by almost 120% compared to 2016.

The haigui are back to build a world power

Today, China is the world’s second largest economy in terms of nominal gross domestic product, and the largest country by the size of export and foreign direct investments. It keeps investing more and more (Worldbank, 2020) in Research and Development (R&D), and Chinese employers recruit in sectors such as high technology, IT, telecommunications, finance, law, consulting, etc. (Jiang, 2016). As a result, China has become an attractive country for young and ambitious people returning from abroad, offering working and living conditions comparable even with those in the West.

In Benjamin Carslon’s “How China’s ‘sea turtles’ will crush the US economy” (The World, 2012) we find examples of Chinese natives who have abandoned their careers in the United States and returned to their homeland to contribute to the development of the Chinese economy. After having worked in top American companies, gifted and armed with knowledge, they return to the country and are remarkably successful. According to a study by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, “over 80 percent of Chinese who returned said that there were more opportunities at home than in the US.”

The authors of the article point out that China’s most popular search engine Baidu was founded by a haigui, Robin Li. The company is one of the most coveted jobs among students at China’s top universities and attracts talent from Silicon Valley as well. Fan Li is currently an executive director of network infrastructure and cloud computing at Baidu. After graduating from Shanghai Fudan University, she studied at the University of Ohio and the University of Wisconsin. She then worked at Cisco and Google during the time when these tech giants rose to their current heights. Fan Li returned for two reasons. She wanted to be closer to her parents, but also felt it was the right time to transform her knowledge into experience in China. According to the Ewing Marion Kauffman Survey, more than half of responders said that China’s economic development was an important motivating factor for them to return.

Wang Mengqi, who graduated in computer science from UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) with a master’s degree, decided to return with her husband, another “overseas Chinese”, working at IBM. Upon their return, Wang has been named the vice president responsible for consumer products in Baidu. She doesn’t think she would have had similar prospects in the US. “Just last month, I went back to Silicon Valley to visit some friends. What I found out is they are doing the same things they were doing ten years ago. Nothing has changed. They are smart people, but they cannot get enough opportunities in the US.”

Although, as the authors of the study stress, the Great Firewall of online censorship does not make work easier, and Chinese technology companies are still better at imitation than innovation (the examples listed are YouTube, Twitter and Facebook, whose counterparts are YouKu, Sina Weibo, and RenRen), China continues to offer great opportunities for career development in technology sector. After all, it has more than 500 million internet users. Here, haigui have a chance to take part in making history and building China’s power.

Expectations vs reality

Haigui would seem to have a bright future in China, that rewards their financial investment and effort put into getting education abroad. But while the 1990s were unquestionably a golden era for overseas graduates, many question whether the good times continue today. In 2020, more than 800,000 Chinese students, more than ever, have returned to their home country (South China Morning Post, 2020a). That’s also more than 70% more than the previous year. This may have been influenced by tightening migration regulations, as well as by the coronavirus pandemic. But due to the slowdown in economic development, fewer new jobs are being created, thus competition is increasing.

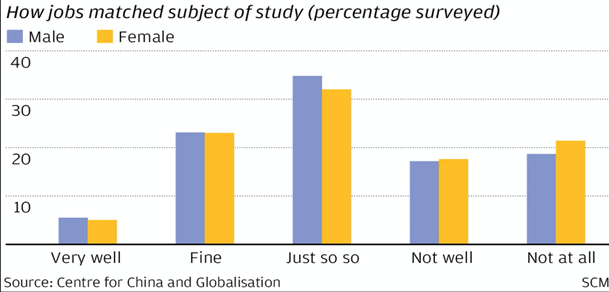

In 2018, a Beijing-based think-tank Centre for China and Globalisation surveyed 2,000 Chinese students returning home. It found that 80% of them earned less than they previously expected and 70% performed work that was not related to their skills and experience (South China Morning Post, 2020b).

As a former US college student Owen Wang reports: “Headhunters told me that the big firms would want to hire former employees of top companies such as Google and Facebook. As for the small ones, they cannot afford haigui.” (South China Morning Post, 2020b). That’s why many haigui have to compromise by agreeing to lower-than-expected wages or by changing industries.

Most internship and job offers come at the end of the Chinese academic year, so there’s little left for those who are late to return from abroad. It turns out that their compatriots educated in the country do not at all lag behind in terms of knowledge about new technologies. In addition, haigui do not have equally extensive networks of contacts (关系 guānxi), which makes it much more difficult to enter some industries on the local market. A spokesman for the European Union Chamber of Commerce in Beijing told South China Morning Post: “In conversations on the topic, members do mention a growing preference among companies for recruiting local talent with international education, rather than junior expat profiles that may leave the country one day” (South China Morning Post, 2019).

A separate issue is a potential cultural shock. As the countries where haigui complete their education allow greater personal freedom and unrestricted access to information, limits and censorship in China may come as a surprise to them. In addition to that, when it comes to financial issues, young people in China are accustomed to parents, as a rule, covering the costs of their education. In the United States, however, students take loans to cover tuition and move out of their parents’ homes quite early. Having two “homes” can also cause them not to settle anywhere for good and constantly confront the feeling of being “strangers”. While in the West it is important to develop individualism, in China collectivism is valued more. All of these cultural, economic and political differences can lead to a “personality crisis”. A 2015 Center for China and Globalization survey found that 68% out of 918 haigui ultimately decided to return to the country where they earned their degree and stay there (Radiichina, 2020).

Conclusions

As a result of their growing numbers, haigui have begun to lose their market value, and many have trouble finding jobs or earn less than expected. Soon, new terms that reflect this reality have entered the dictionary of modern Chinese. The first is haidai (海待 hǎidài), which is a homonym to “sea weed” and refers to a Chinese who has returned to the country but cannot find a job (South China Morning Post, 2017). The second is zai gui hai (再归海 zài guī hǎi) which literally means “to return to the sea” (Radiichina, 2020) and describes a haigui who decided to return to the place of their education due to lack of prospects in China.

In 2013, Chinese president Xi Jinping urged talented Chinese, both those at home and abroad, to build with him a “dream of national rejuvenation”. As the Centre for China and Globalisation points out, “employers had to do more to address the widespread discontent among haigui”. Government institutions, on their part, should put more work into the promotion of programmes aimed at returning Chinese people. According to the survey, 60% of them were unaware of the potential benefits (South China Morning Post, 2020b).

Haigui undoubtedly possess great potential to help China’s economic development. As The Economist claims, “Sea Turtles are helping to link China’s economy to the world. They founded leading technology firms such as Baidu. Many are senior managers in the local divisions of multinationals. They are helping to connect China to commercial, political and popular culture abroad” (Rzeczpospolita, 2020). It is thanks to them that China is now second only to the US in terms of overall scientific output. Haigui play the role of the leaders in Chinese society and occupy significant positions in the institutions of higher education, thanks to which future generations could have a chance to come into contact with modern, liberal ideas (Jiang, 2016). As the President of Center for China and Globalization, Wang Huiyao, says: “Chinese overseas–educated scholars will continue to play a vital role in promoting the country’s transformation into an innovation-driven economy in the next three decades” (Jiang, 2016).

Przypisy:

2017 sees increase in number of Chinese students studying abroad and returning after overseas studies (2018). Ministry of Education of The People’s Republic of China. Available at: <http://en.moe.gov.cn/news/press_releases/201804/t20180404_332354.html> [Access: 7.1.2021].

Ambasador Chin: Test globalnego systemu (2020). Rzeczpospolita. Available at: <https://www.rp.pl/Koronawirus-2019-nCoV/200319216-Ambasador-Chin-Testglobalnego-systemu.html> [Access: 19.12.2020].

As sea turtles turn into seaweed, Chinese graduates look beyond the career ladder to find value in studying abroad (2017). South China Morning Post. Available at: <https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/2111411/sea-turtles-turn-seaweed-chinese-graduates-look-beyond-career> [Access: 9.1.2021].

China’s crowded labour market is making life tough for foreign workers and new graduate ‘sea turtles’ (2019). South China Morning Post. Available at: <https://www.scmp.com/economy/chinaeconomy/article/2185133/chinas-crowdedlabour-market-making-life-tough-foreignworkers> [Access: 9.1.2021].

China’s overseas graduates return in record numbers into already crowded domestic job market (2020a). South China Morning Post. Available at: <https://www.scmp.com/economy/chinaeconomy/article/3102384/chinas-overseasgraduates-return-record-numbers-already> [Access: 9.1.2021].

Full Text of Jiang Zemin’s Report at 14th Party Congress (2011). Beijing Review. Available at: <http://www.bjreview.com.cn/document/txt/2011-03/29/content_363504_6.htm> [Access:8.1.2021].

How China trained a new generation abroad (2008). Scidev Net. Available at: <https://www.scidev.net/global/features/howchina-trained-a-new-generation-abroad/> [Access: 1.3.2021].

How China’s “sea turtles” will crush the US economy (2012). The World. Available at: <https://www.pri.org/stories/2012-08-06/howchinas-sea-turtles-will-crush-us-economy> [Access: 10.1.2021]

Jiang, X. (2016). Haigui (Overseas Returnee) and the Transformation of China. Migration in East and Southeast Asia, 47-68. More Chinese students return to China after obtaining degrees overseas (2020). China Daily. Available at: <https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202012/14/WS5fd75609a31024ad0ba9bc3e.html> [Access: 6.1.2021]

Research and development expenditure (% of GDP) – China (2020). Worldbank. Available at: <https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GB.XPD.RSDV.GD.ZS?locations=CN> [Access: 1.3.2021]

The Overall Situation of Studying Abroad (2009). Ministry of Education of The People’s Republic of China. Available at <http://en.moe.gov.cn/cooperation_exchanges/201506/t20150626_191376.html> [Access: 9.1.2021]

Why China’s “Sea Turtles” Face Inner Struggles After Returning to Home Shores (2020). Radiichina. Available at: <https://radiichina.com/china-sea-turtlesexistential-struggles/> [Access: 2.1.2021]

Why China’s overseas students find things aren’t always better back home (2020b). South China Morning Post. Available at <https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/2162229/why-chinas-overseas-students-findthings-arent-always-better-back> [Access: 9.1.2021]

Zweig, D., Changgui, C., & Rosen, S. (2004). Globalization and Transnational Human Capital: Overseas and Returnee Scholars to China. The China Quarterly, 179, 735-757. Cambridge University Press

Ewelina Horoszkiewicz PhD candidate in Political Science at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, where she studies the role of expert networks in transnational politics, with a particular focus on EU–China relations. She also works on issues of scientific collaboration and knowledge security in Europe–China relations. She holds degrees in International Relations from Renmin University of China in Beijing, as well as in Sinology and Management from the University of Warsaw.

czytaj więcej

80th anniversary of Indonesian Proclamation of Independence and 70th anniversary of Poland-Indonesia diplomatic relations. April 23rd, at 10:00 am, aula im. prof. Waldemara Michowicza, ul. Lindleya 5A, Łódź.

“Green growth” may well be more of the same

Witnessing the recent flurry of political activity amid the accelerating environmental emergency, from the Green New Deal to the UN climate summits to European political initiatives, one could be forgiven for thinking that things are finally moving forward.

Dawid JuraszekOnline Course: “Educational tools for addressing the effects of war”

The Adam Institute for Democracy and Peace is offering “Betzavta” facilitators, middle school and high school educators, social activists, communal activists and those assisting refugees an online seminar to explore educational issues related to wartime.

Indian dream – interview with Samir Saran

Krzysztof Zalewski: India is a large country, both in terms of its population and its land area, with a fast-growing economy. It is perceived as a major new player on the global stage. What would the world order look like if co-organized by India? Samir Saran: India’s impact on the world order is already significant, but […]

Krzysztof ZalewskiAn “Asian NATO”: Chances and perspectives

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has reinvigorated NATO. Can the Chinese pressure on its neighbours, especially Taiwan, create an Asian equivalent of NATO?

Paweł BehrendtThe strategic imperatives driving ASEAN-EU free trade talks: colliding values as an obstacle

Recently revived talks aimed at the conclusion of an inter-regional free trade agreement between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the European Union (EU) are driven by strategic imperatives of both regions.

Robin RamcharanDr. Nicolas Levi with a lecture in Seoul

On May 24 Dr. Nicolas Levi gave a lecture on Balcerowicz's plan in the context of North Korea. The speech took place as part of the seminar "Analyzing the Possibility of Reform and its Impact on Human Rights in North Korea". The seminar took place on May 24 at the prestigious Yonsei University in Seoul, South Korea.

A Story of Victory? The 30th Anniversary of Kazakh Statehood and Challenges for the Future.

On 25 May 2021, the Boym Institute, in cooperation with the Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, organised an international debate with former Polish President Aleksander Kwaśniewski (1995-2005).

Lessons for China and Taiwan from the war in Ukraine

The situation of Taiwan and Ukraine is often compared. The logic is simple: a democracy is threatened by a repressive, authoritarian regime making territorial claims and denying it the right to exist.

Paweł BehrendtThis is the second part of an inquiry into Ulaanbaatar’s winning 2040 General Development Plan Conception (GDPC). In this part of paper, I look into some of the plans and/or solutions proposed in Ulaanbaatar’s 2040 GDPC.

Paweł SzczapLiquidation of the Polish colony in Manchuria (north-eastern China)

Ms. Łucja Drabczak - A Polish woman born in Harbin, she spent her childhood in China. She returned to Poland at the age of 10. She is the author of the book 'China... Memories from my childhood'. She contacted us to convey special family memories related to leaving Manchuria in 1949.

Chinese work on the military use of artificial intelligence

Intensive modernization and the desire to catch up with the armed forces of the United States made chinese interest in the military application of futuristic technologies grow bigger.

Paweł BehrendtOnline Course: “Conflict Resolution and Democracy”

The course will be taught via interactive workshops, employing the Adam Institute’s signature “Betzavta – the Adam Institute’s Facilitation Method“, taught by its creator, Dr. Uki Maroshek-Klarman. The award-winning “Betzavta” method is rooted in an empirical approach to civic education, interpersonal communication and conflict resolution.

Online Course: “Feminism and Democracy: a Deep Dive”

The course will be taught via interactive workshops, employing the Adam Institute’s signature “Betzavta – the Adam Institute’s Facilitation Method“, taught by its creator, Dr. Uki Maroshek-Klarman. The award-winning “Betzavta” method is rooted in an empirical approach to civic education, interpersonal communication and conflict resolution.

Women in Public Debate – A Guide to Organising Inclusive and Meaningful Discussions

On the occasion of International Women's Day, we warmly invite you to read our guide to good practices: "Women in Public Debate – A Guide to Organising Inclusive and Meaningful Discussions."

Ada DyndoAt the Boym Institute we are coming out with new initiative: #WomeninBoym, which aims to show the activity of this – often less visible – half of society. We will write about what women think, say and do. We will also publicise what women are researching and writing.

WICCI’s India-EU Business Council – a new platform for women in business

Interview with Ada Dyndo, President of WICCI's India-EU Business Council and Principal Consultant of European Business and Technology Centre

Ada DyndoAn interview with Mr. Meirzhan Yussupov, Chairman of the Board of the “National Company” KAZAKH INVEST” JSC - Member of the Board of Directors of the Company

Magdalena Sobańska-CwalinaOnline Course: “Conflict Resolution and Democracy”

The course will be taught via interactive workshops, employing the Adam Institute’s signature “Betzavta – the Adam Institute’s Facilitation Method“, taught by its creator, Dr. Uki Maroshek-Klarman. The award-winning “Betzavta” method is rooted in an empirical approach to civic education, interpersonal communication and conflict resolution.

Invest and cooperate with Serbia or Poland? A dilemma for South Korean companies

This paper explains why Serbia may replace Poland as a strategic outsourcing centre for South Korean companies in Central and Southern Europe.

Nicolas LeviFrom quantity to quality. Demographic transition in China – interview with Prof. Lauren Johnston

What we observe in China is a population reduction strategy paired with the socio-economic transition. In my view it’s not a crisis, but it is a very challenging transition.

Lauren JohnstonRisk and oppportunities for self-driving vehicles. Exploring global regulations and security challenges in the future of connected vehicles. The report was co-produced by Boym Institute and 9DASHLINE.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak and emerging contractual claims

With China one of the key players in the global supply chain, supplying major manufacturing companies with commodities, components and final products, the recent emerging outbreak of Coronavirus provides for a number of organizational as well as legal challenges.

Book review: “North Korea’s Cities”

Book review of "North Korea’s Cities", written by Rainer Dormels and published byJimoondang Publishing Company in 2014.

Nicolas Levi