First burials of Catholics, mostly Poles but also other Non-Orthodox believers took place in future Harbin in the so called small „old” or later Pokrovskoe Orthodox cemetery in the future European New Town quarter and small graveyards at the military and civilian hospitals of Chinese Eastern Railway at the turn of XIX and XX century.

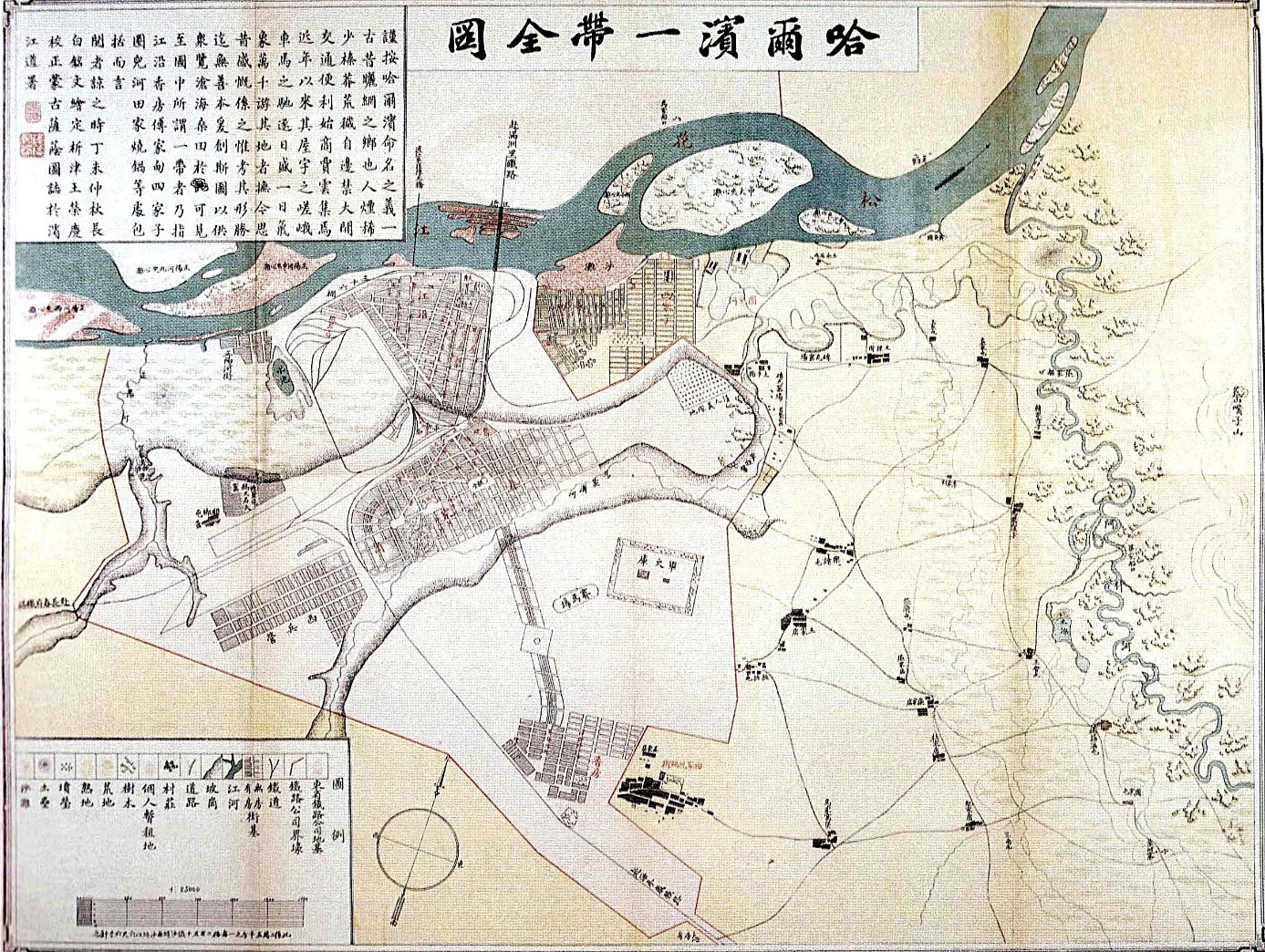

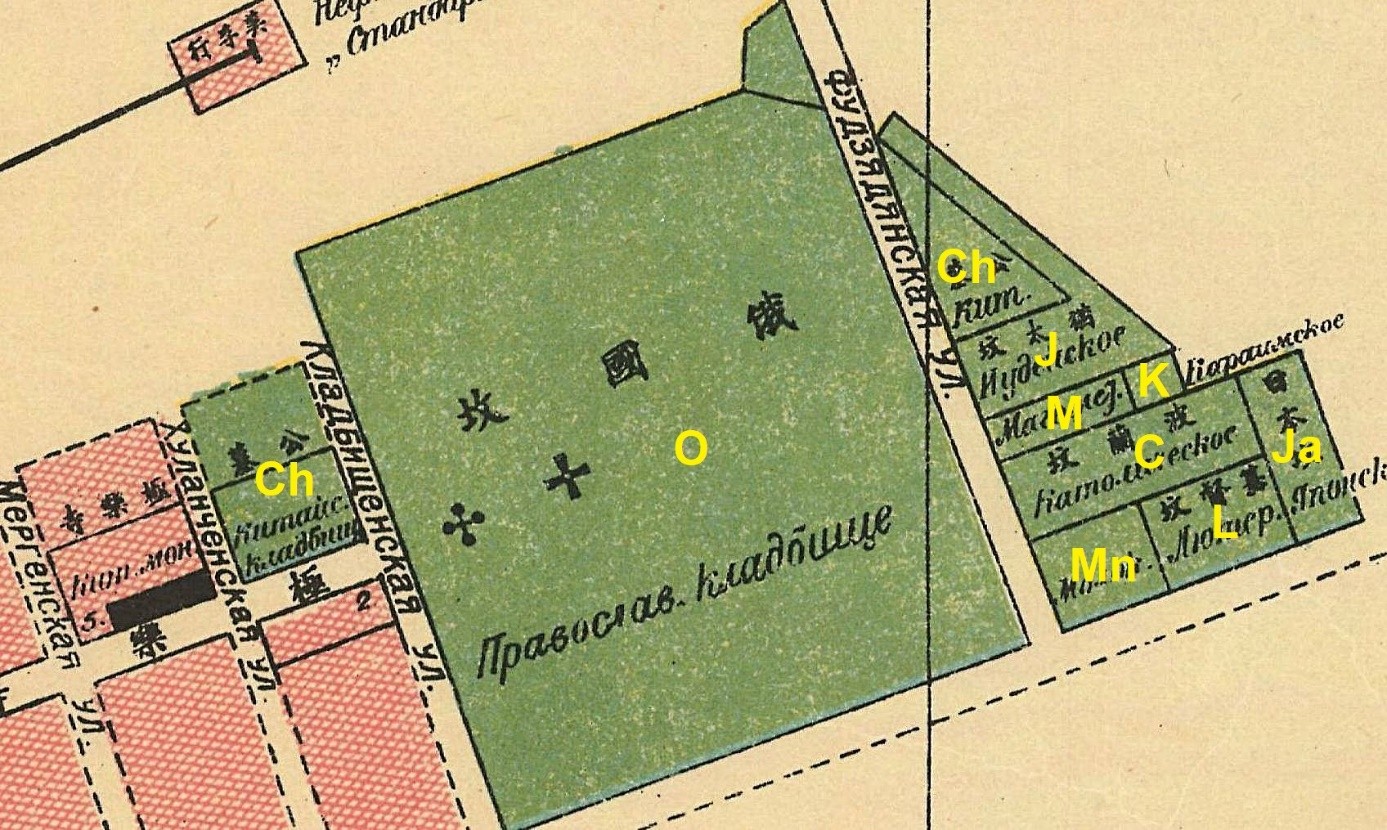

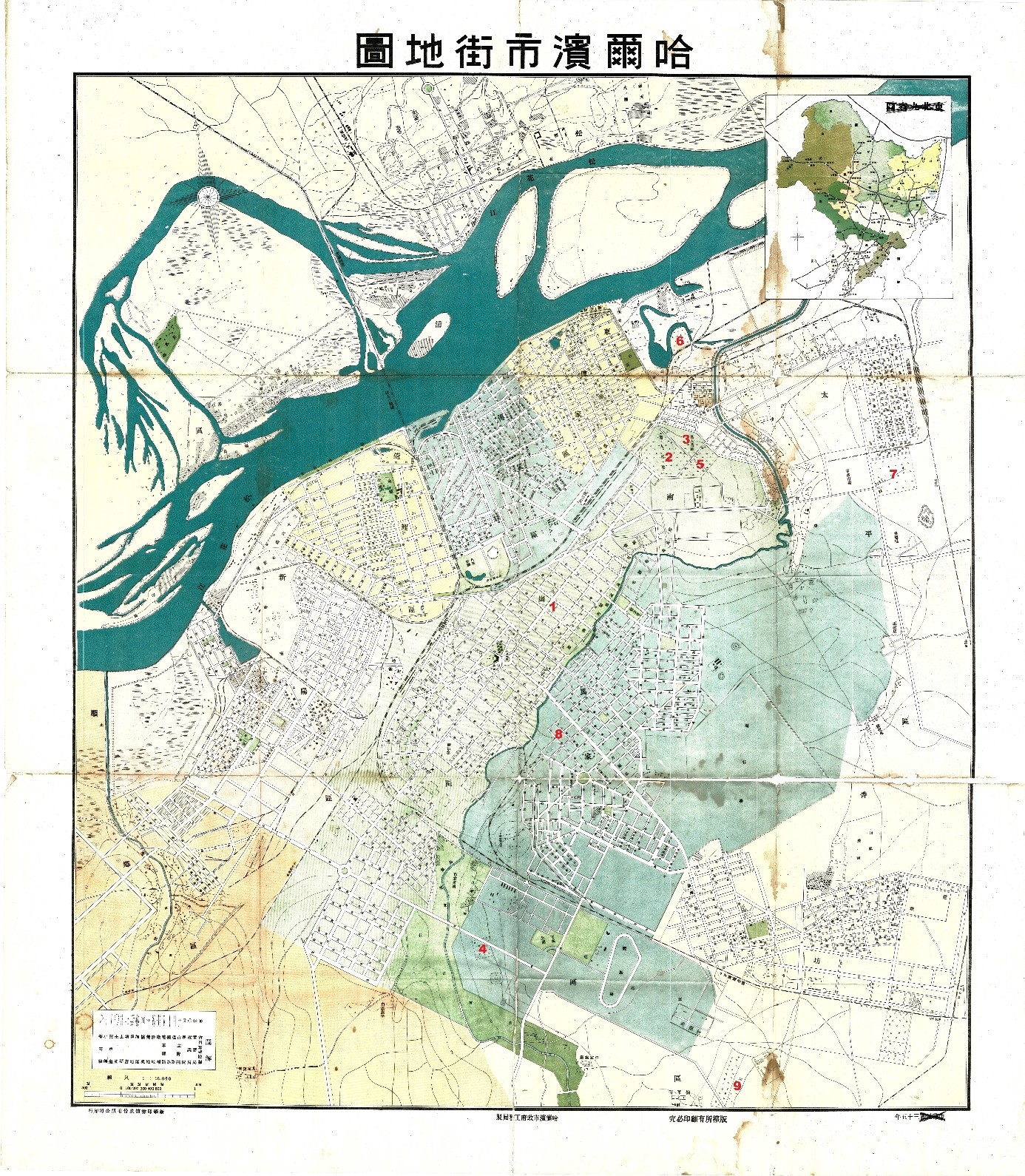

The general plan of the new town Sungari (later Harbin) prepared in 1899 (il.a) provided for the new bigger town cemetery with the area of about 42 hectares (100 acres). It was located about 3,5 km east from St. Nicolas Orthodox cathedral, icon of the town, in the centre of European Harbin. In 1902 the new Orthodox cemetery was opened there with the area of about 29,5 hectares (71 acres) and a shape of a square. Here ended the main street, Grand Prospect avenue. In the next year 1903, cemetery for the Non-Orthodox was staked out east of the Orthodox one with an area of about 12,5 hectares (30 acres) and a shape of a triangle. Both burial-grounds were divided by the so-called Fujiadian inner cemetery road (i.e. road leading NW to Chinese suburb of the same name). The Non-Orthodox graveyard (in Chinese literature named United Cemetery of Seven Countries – UCSC) consisted of the Catholic, Jewish, Lutheran, Moslem, Japanese, Karaite (Jewish sect), Molokan (Orthodox sect) and Chinese cemeteries. (il.b)

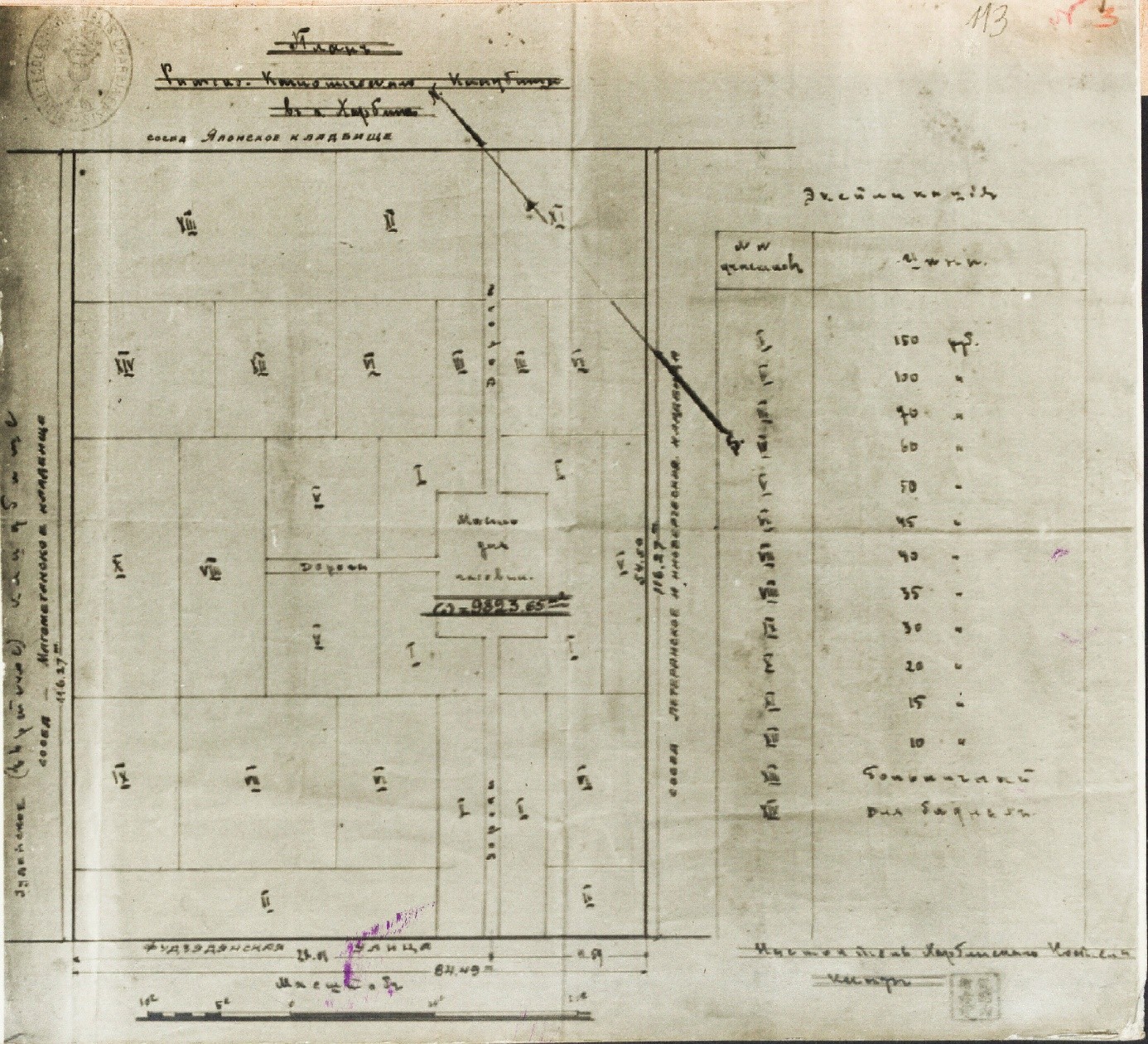

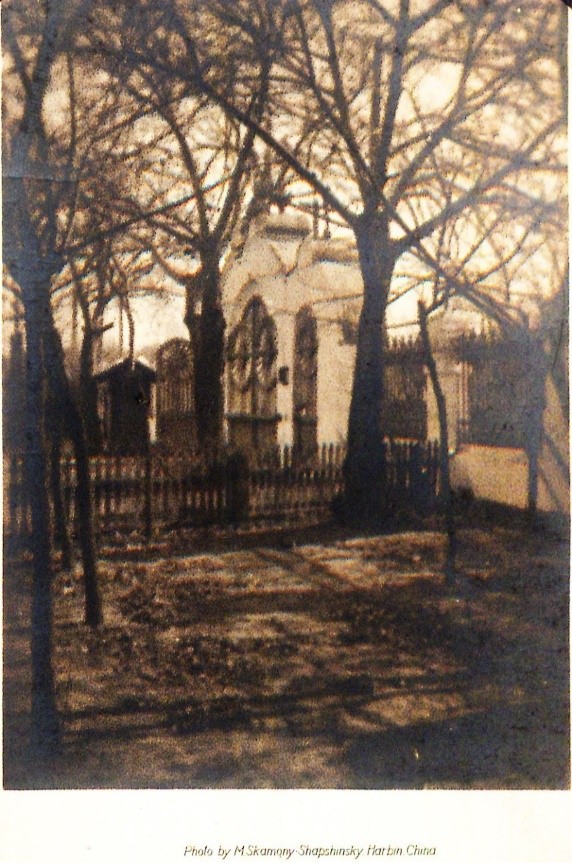

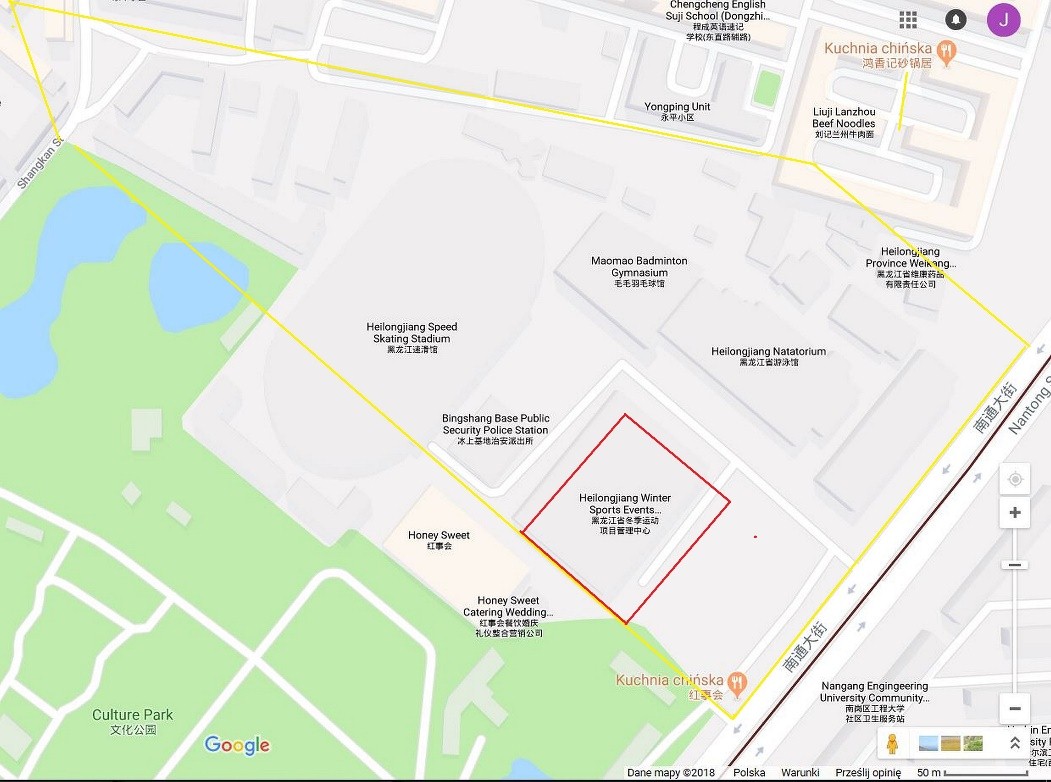

Catholic cemetery (il. c) of an area 9.824 square metres (84,49×116,27 m) with a shape of a rectangle (c) was located in the SW part of the graveyard with entrance (il.d) from Fujiadian road (il.e). It bordered with Moslem, Karaite, Japanese, Lutheran and Molokan graveyards. It was divided in three parts by the inner road leading from the entanrce through small central place in the middle that ended at the Japanese cemetery fence. The small road north of the central place completed the communication. There were 25 burial places of different prices paid for the grave. The most expensive ones were around the central place and by the road at the entrance (150 Roubles i.e. 75 $) then by the fence at Fujiadian road (100 Roubles). The rest from 70 to 10 Roubles per grave were located farther off the central place towards the inner circumference fence. Two burial places in the farthest NW corner were for the poor and hospital deceased.

Until erection of the cemetery, the deceased Poles (also other Catholics like Lithuanians, Czechs, Austrians, Hungarians) were buried in 1898 – 1902 in the Orthodox „old” cemetery, then since 1903 until 1907 in allotted plot by Catholic priests coming on pastoral visits to Harbin from Vladivostok in Russia, that took over for a few years the religious service for its faithful along CER expropriated land. They were : army chaplain Fr. Adam Szpiganowicz, Fr. Piotr Silowicz, Fr. Piotr Bulwicz, Fr. Stanisław Lawrynowicz and Fr. Franciszek Janulaitis. Sometimes also French missionaires that worked among Chinese (Mission Étrangères de Paris – MEP) from nearby Hulan (Fr. Jean-François Souvignet) or later priest from the catholic center with church, orphanage and infirmary (Maison de bon Pasteur) of the French nuns Franciscaines Missionaires de Marie – FMM, built in 1905 in Fujiadian, then Chinese part of Harbin (now Daowai), gave the last rite.

Marriages, Birth and Death records until 1907 were kept in Vladivostok RC church and Fujiadian church of FMM. First permanent Harbin RC chaplain was Fr. Antoni Maczuk, who began in 1906 to systematically carry on all church records, that were kept in the vicarage of St. Stanislas Bishop the Martyr temple (solemn dedication in September 1909). The church satisfied religious need of Catholics in the whole area of the CER expropration land as well as the Northern Manchuria until 1923. From 1924 the second RC new church of the St. Jozaphat Bishop the Martyr in Pristan district of Harbin (now Daoli), took over the CER land from Manchuli, the most western railway station to northern districts of Harbin. The rest of Harbin and railway stations east (to Suifenho station) and to the south (to Kuanchendze – Changchun station) was left to St. Stanislas BM church. The chaplains of both churches were : Fr. Wladyslaw Ostrowski, Fr. Aleksander Eysymontt, Fr. Antoni Leszczewicz, Fr. Witold Zborowski, Fr. Pawel Chodniewicz and Fr. Gracjan Kolodziejczyk.

Church records carried out from 1906 until 1957 surviwed and were taken out of China to Australia by the last two Polish priests, Fr. Aleksander Eysymontt (last vicar of the St.Stanislas BM church) and a Franciscan, Fr. Gracjan Kolodziejczyk (last vicar of the St. Jozaphat BM church). The last years of their presence in Harbin it was the religious service to the mostly Chinese Catholics (less than a hundred Poles were staying then still in Harbin) that flocked to Polish churches when the French church for Chinese in Fuijadian was closed down by local authorities. Both priests did not agree to join the newly established Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association as an government controlled semi-religious body for Catholics in the mainland China (except of Taiwan) and were forced to leave China at the end of March 1957. The records were transferred from Australia to Poland in 1990-ties and are lodged now in the Archive of the Catholic Order of the Christ Association (Archiwum Towarzystwa Chrystusowego) in Poznan.

The death records show the social strata of the deceased, sex, age, place of birth and cause of death according to the formal Russian register book pattern (used in Orthodox churches – Chast’ Tretiia o Umershikh). Since 1928 the entries in Russian language was replaced with Latin. The form was also changed into the Latin register book (Liber Defunctorum), used by Catholic missionaries in China, with the pattern of entries in more laconic form than in the previous one.

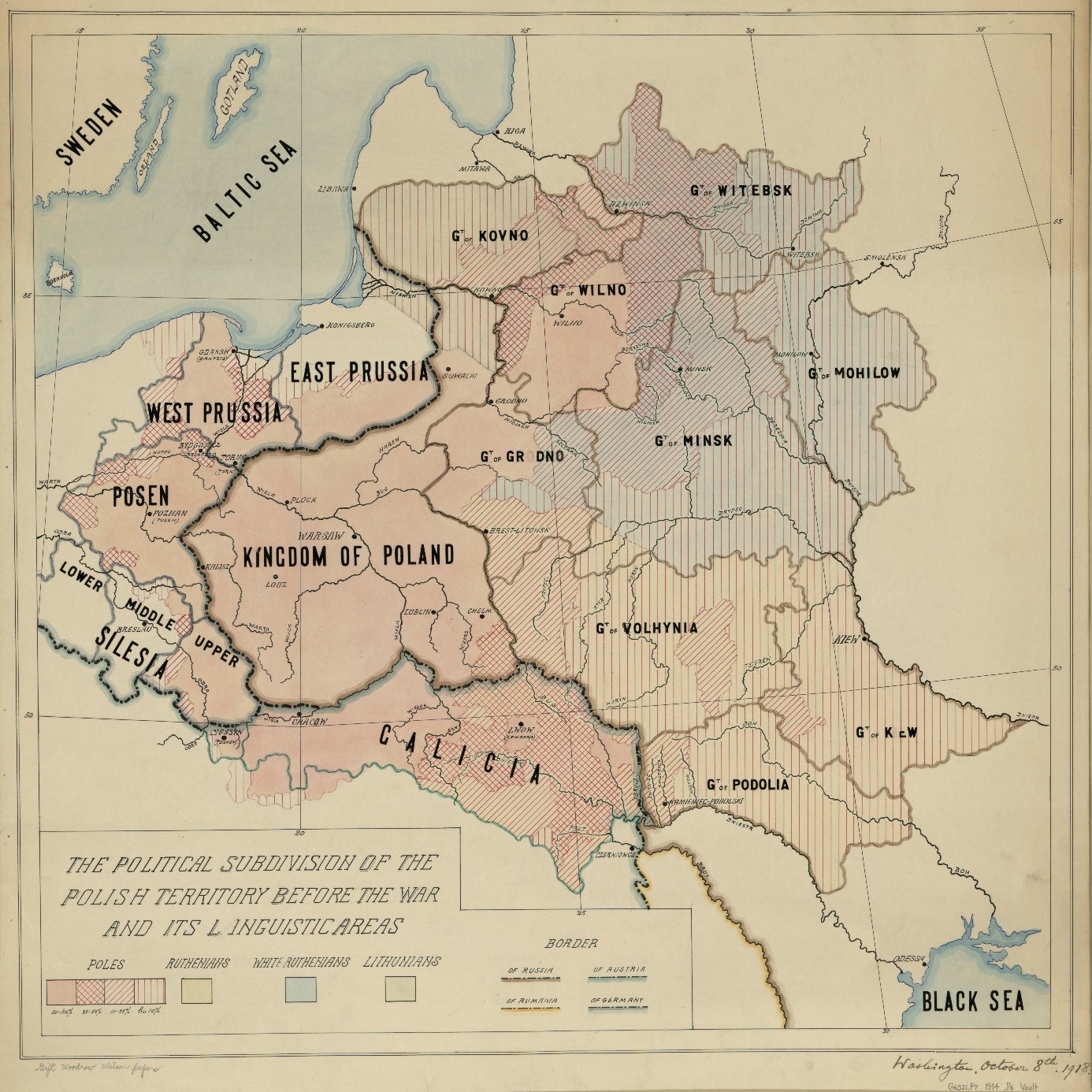

Data taken from the records, regarding the place of birth of the deceased (about a thousand persons with full data) shows the picture of the emigrants whereabouts before moving out from the territory of the pre-partition Poland annexed by Russia, Germany (Posen and West Prussia) and Austria (Galicia) at the end of XVIII century. The Russian booty was 80% of its territory, i.e. 580.000 sq. km that at the beginning of XX century was divided roughly in three bigger administrative units.(il.f) The smallest in the west was so called Kingdom of Poland (Tsarstvo Polskoe, later after suppresing of the Polish Uprising 1863 renamed as Privislinskii Krai – Vistula Country) that was divided into 10 small governorates (guberniias). The NW Country (Severo-Vostochnii Krai) a much bigger entity (roughly the territory of previous Grand Duchy of Lithuania) consisted of six big governorates (Wilno, Kowno, Minsk, Mohilow, Grodno, Witebsk). The SW Country (Iuzhno-Vostochnii Krai) or „Polish” Ukraine had three governorates (Podolia, Volhynia and Kijow). The governorates in those Countries were sometimes also called Polskiie gubernii (Polish gubernias) and by Poles Ziemie Zabrane (Taken Land). That territory was also the main bulk of the so called Jewish Pale of Settlement, where most of the Russian (previously Polish) Jews were allowed to live.

Most of the deceased (51%) came from NW and SW Countries (Ziemie Zabrane), mostly from Wilno, Kowno (also Lithuanians) and Podolia Gts. The share of the Kingdom of Poland (37%) was mostly from Warsaw, Lublin and Siedlce Gts. The rest 12% of Polish Catholics orginated from the Russian towns like Odessa, Vladivostok, Riga and St. Petersburg. Rest of Polish territories in German/Austrian hands were represented only by a few persons (mostly former POW from Austrian and German armies).

The social status of deceased with 34% of burghers , 20% of petty gentry and 46 % of peasants, shows greater mobility of the first two categories in comparison to peasants that were mostly young soldiers of Transamur Border Guard Railway Brigades or those Polish and Lithuanian conscripts in the Russian army that remained in Manchuria after Russo-Japanese war 1904-1905.

The data from both Harbin Catholic churches on number of all deceased Catholics, buried in Harbin and CER railway stations between 1898 and 1907 kept in church records of the Vladivostok and Fudjiadian parishes are not currently available or lost. It can be roughly estimated statistically in a way of average mortality in Harbin parish in 1908-1914 for about up to 200 persons. This includes mostly the fatalities during CER construction (there were many graves with inscription „died during construction”), soldiers of CER Railway Guard that fell when putting down the Boxer Uprising in 1900 in Manchuria, handful of wounded soldiers of the Russo-Japanese war that died in military hospitals in Harbin and civilians that came to Harbin after completing CER in 1903.

Thus, the number of all Catholics buried in Harbin (also in „old” or Pokrovskoe cemetery) according to the church records 1907-1957 (2.019) and estimation for 1898-1907 (200) can be assumed for about 2.220 persons. Most of them were Poles (88% – 1.950 persons) then came Lithuanians (75 persons), Czechs ( 50 persons), Germans/Austrians (35 persons), Chinese (20 persons), Armenians (20 persons), Japanese (20 persons), Hungarians ( 15 persons), French (15 persons), Italians (10 persons), English/Americans (5 persons), Koreans (5 persons).

Some of the buried Poles from Kingdom of Poland were soldiers (64 persons) of the Transamur Border Guard and two batallions of the Railway Brigades (Warsaw and Baranowicze). They were young persons at the age of 21 to 24 years old died mostly because of tuberculosis, other diceases and fatalities. Also some POW’s from Austrian (also Czechs and Hungarians), German and Turkish (Armenian and Persian) armies that died in Harbin hospitals were buried here. The level of sanitary conditions at the first years of Harbin existence was very low, reflected in high mortality rate of infants (up to a year old). In the years of 1907-1910 and 1914-1916 the rate was almost 30% of all deceased. Then in the years 1919-1923 got next peak of almost 20% of deceased. This time it was the result of poor living condition of the refugees from the Soviet Russia that flocked to Manchuria. During those years also the number of deceased got its high.

The cemetery also took four veterans of the Polish Uprising 1863 that were exiled to Siberia and in an old age got to Harbin. Also one of the soldiers of the Polish 5th Polish Rifle Division that could break through the bolshevik encirclement in Siberia. These were buried at the cost of Polish diplomatic mission in Harbin.

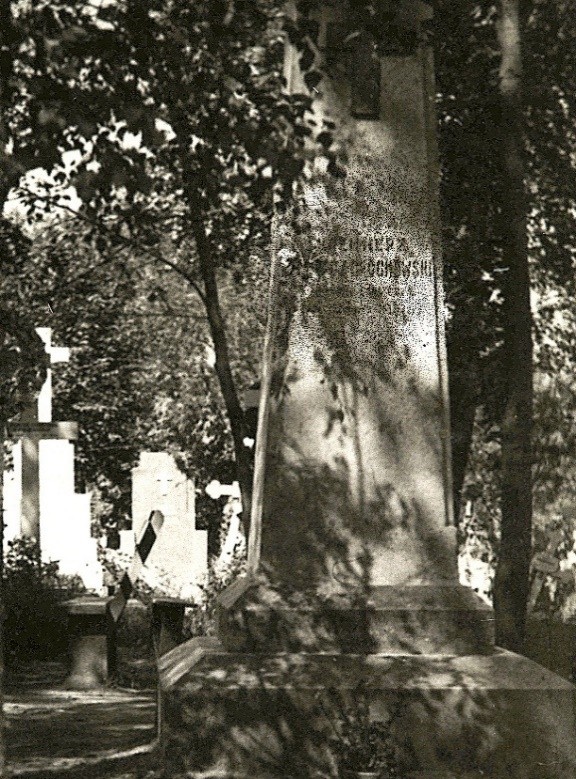

Some of prominent members of the Polish community had their final place of rest in Harbin „old” Orthodox cemetery (il.g). The wilderness of Manchuria took its toll among already mentioned engineers, technicians and workers that died during construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway from exhaustion, accidents and diseases. Civil engineer, Jan Gerszow (1849-1900), Polish Lutheran, died from exhaustion at the end of 1900 in Fulaerdi by Tsitsikar (Qiqihaer). He was the head of the exploration and construction distance in the western part of CER. Then it was civil engineer, Nicolai Kazy-Girei (1870-1917) (h) , Russian Tatar, architect of the Catholic church in Neo-Gothic style, died in 1917. It is also the resting place of civil engineer, Jan Oblomiewski (1871-1924) (il.i), Catholic, Russified Pole, who was town chief engineer at the beginning of Harbin construction, that commited suicide in 1924. In 1927 here was buried Jan Pawlewski , Orthodox, Russified Pole from Podolia, one of the pioneers of CER construction. Walenty Wels, civil engineer in service at the very beginning of CER construction, died in 1933. He was Polish Lutheran, supervised the construction of catholic church in Harbin (his wife Zofia took active part in the life of Polish community). Also to mention is Barbara Zaloga (1847-1931) very active president of the Ladies Conference of St. Vincent de Paul Association that took care of Polish orphans in both girls and boys dormitories in Harbin.

Among buried in the Harbin Catholic cemetery were two deserving vicars of St. Stanislas church, Fr. Wladyslaw Ostrowski (1874-1936) (il.j) in 1936 and Fr. Pawel Chodniewicz (1881-1949) in 1949. They were religious, moral and national guides for the Polish community. First was the founder of the Polish grammar and high school in Harbin. Both were buried by the church itself. Then Fr. Witold Zborowski (1899-1948) (il.k), the vicar of the second Catholic church in Pristan suburb that died in 1948 shot accidentally by Chinese sentry. Other distinguished Poles that have to be commemorated include Edmundd Doberski (1868-1920), president of „Gospoda Polska” Association that tireless efforts made it possible to build its seat died from exhaustion in 1920, Gustaw Emeryk (1855-1933), industrialists also president of „Gospoda Polska” died in 1933, engineer Edward Kajdanski (1872-1936), member of „Gospoda Polska” Association, technical manager in Acheng sugar refinery that died in 1936. Next 1937 year died mining engineer, Kazimierz Grochowski (1873-1937) (il.m), renown explorer and archeologist, headmaster of the Polish High School and member of the Manchuria Research Society in Harbin. In 1939 Jan Wroblewski (1869-1939), founder of the first European brewery in China was buried here. This same year died civil engineer, Aleksander Miaskowski (1866-1939), proficient architect of many buildings in Harbin (inter alia famous Matsuura universal store in Neo-Baroque style). The next 1940 year saw the burial of the pioneer of the Manchurian timber industry, Wladyslaw Kowalski (1870-1940) (il. l) „King of Manchurian forests”, benefactor of the Polish community as well as of the scientific (Harbin Polytechnical Institue and Manchuria Research Society) and commercial (Harbin Chamber of Commerce) enterprises in Harbin . In 1946 died in Acheng Mikolaj Kossakowski (1884-1946), technical director of the sugar refinery, buried in Harbin cemetery. Albin Czyzewski (1883-1948) (il.n), head of economic department of CER, president of Polish Relief Committee (1941-1945) that died in 1948. When the most of the Poles left Manchuria in 1949 only few hundred stayed in Harbin but that group diminished quickly every year. In 1955 died member of „Gospoda Polska”, Adam Czajewski (1873-1955) (il.o), CER surveyor in Real Estate Department and later last president of CER Polish Pensioners Association.

Most of the burial places were simple earthen graves with wooden or iron crosses. Some more well to do persons had monuments of stone or iron. The cemetery was planted with birch and elm trees.

As for other Catholics buried in Harbin we can mention Czech, Frantisek Hrdlicka (1887-1931), captain of Czech army, diplomat in Czechoslovak mission in Harbin, that commited suicide in 1931. Among other Czechs there were Ferdinand Erml (1869-1948), musician, owner of the second European brewery in Harbin, outspoken representative of the Czech community died in 1948 and Frantisek Vinkler (1884-1956) (il.s) renown sculptor in Harbin, that died in 1956 just before his going back to home country. Tragic fate reached last French consul in Harbin, Jules Leurquin (1886-1945) (il.t) that was gifted by the Japanese Kempeitai in winter 1945 and was buried here. In 1938 an Irish-Russian Catholic aristocrat, Miss Kathleen Ffrench died in Harbin but her body was later transferred to the family grave in Monivea Castle in Ireland before outbreak of the II WW.

Some soldiers-Catholics, i.e. eight Czechs (two buried in Harbin) from the Czech Legion that fell in Manchuria in 1918-1920 ( some victims of the Japanese-Czech shoot-out in the Hailar railway station) were commemorated in Orthodox cemetery with a tombstone (il.u) made by famed local sculptor, Frantisek Vinkler. It was financed by the Czech veteran fund from Prague and unveiled in 1937 in the presence of the Czech community and consul Rudolf Heiny.

There were also smaller groups of Poles scattered along the CER in railway stations that bury their deceased on local Orthodox cemeteries with assistance of the Catholic chaplains coming periodically from Harbin. These amounted to 94 persons, buried mainly in Manchouli (23), Imienpo (13), Handaohezi (10), Hailar (9), Qiqihaer (8), Buhedu (7), Acheng (5) and other eight smaller railway stations (18).

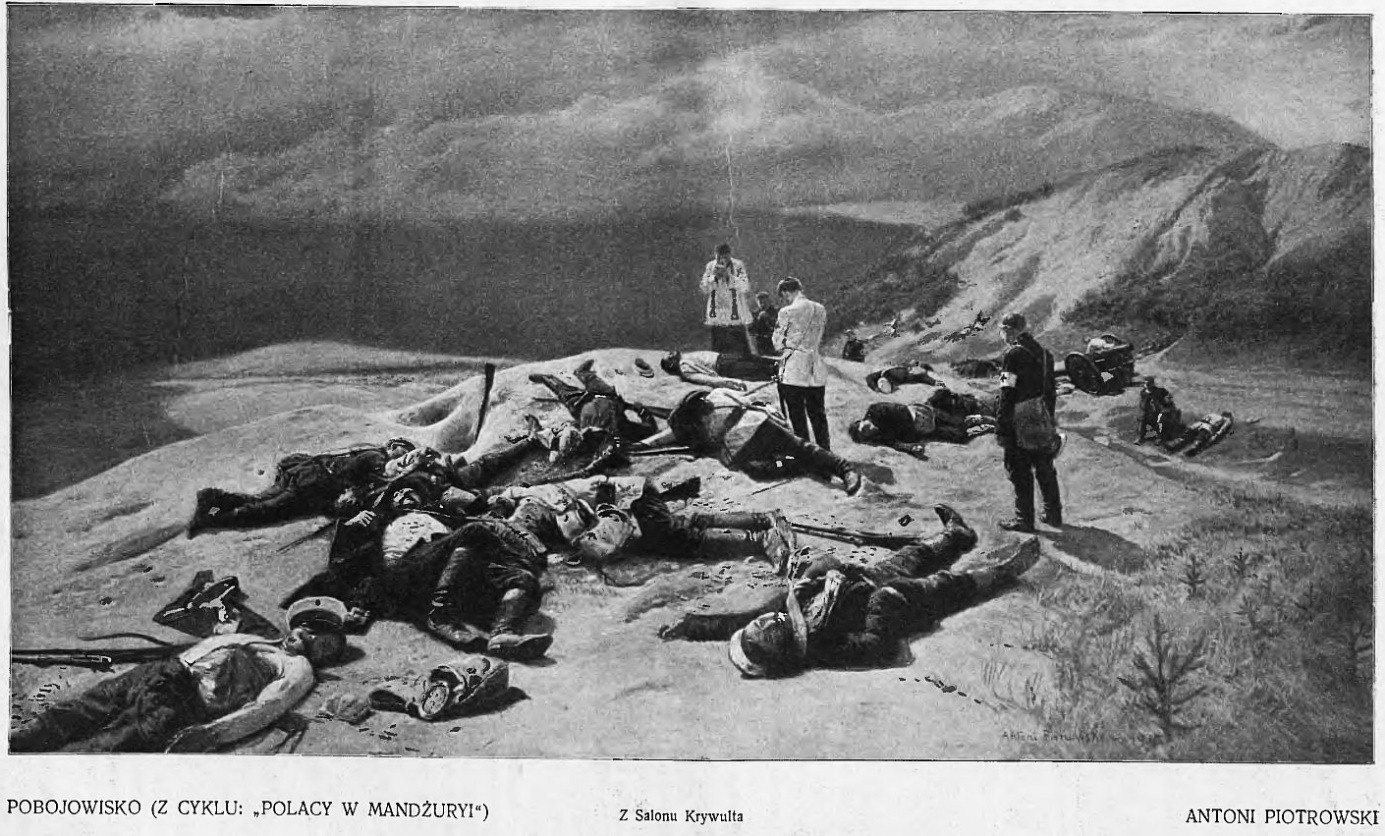

It is also worth to remember many thousands of Poles, forced into the Czarist army peasant-conscripts from Kingdom of Poland and NW Country that fell in southern Manchuria in the 1904-1905 war with Japan in the service of Russian imperialism in the Far East. They were buried with Russians in 18 military cemeteries in nameless mass graves (usually 60 corpses per grave) scattered from Port Arthur (Lushun) in the south to Mukden (Shenyang) in the north. Some dead of wounds or illness had been buried also in Harbin Russian military cemetery set out by the temporary hospitals in Gospitalnii Gorodok in the then outskirts of the city.

Almost forty years later four young Poles from Harbin, students of Engineering faculty of Hong Kong University joined but this time freely Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps when Japanese invaded the town. Two of them, gunners Zygmunt Kossakowski (son of the Acheng sugar refinery technical manager) and Wladyslaw Rudrof fell in fight 25th December1941 defending Fort Stanley. Buried in Sai Wan war cemetery and Stanley military cemetery in Hong Kong.

In 1958 when most of the foreigners left Harbin already, the fate of their cemeteries was doomed. Under the pretext of improving the sanitary conditions and make place for the new developments, Harbin authorities demanded to move out graves into the new municipal cemetery in Huangshan outside of town. The notice to do that was very short and practically impossible to be accomplished by relatives in far away countries. Orthodox, Jews, Catholics and Moslems still living in the town protested but in no avail. There were some „consultations” with representatives of Orthodox, Jews and Catholics but it was just a lip service. The Soviet consulate in Harbin (only one left in town) and Polish communist embassy in Beijing did not help its citizens at all but rather forced them to accept inevitable. In fact only a couple of Poles could move out graves of their relatives into the new location.

The deserted European cemeteries as well as other Chinese graveyards in the town limits were left ravages and greens for some years. The graves were vandalized and robbed by bands of thugs from Fujidian looking for valuables and golden teeth of deceased. The broken tombstones were disposed of and used to strenghthening the Sungari riverbanks (some visible bigger ones were taken away later on).

The ground of the foreign cemeteries was turned into Cultural Park in late 1960-ties that in turn in 1990-ties became Harbin attraction, Amusement Park with carnival rides and giant Ferris wheel. United Cemetery of the Seven Countries plot was developed later from outdoor ice rink into the giant Speed Skating Stadium (OVAL) in 1995 and the building of the Heilongjiang Winter Sports Events Management Center in 1999. The last one occupies the place of former Roman Catholic cemetery. The Molokan, Lutheran and Japanese cemeteries dissapeared under the residential high rise development in 2014. The only vestiges of the former graveyards and deceased are some headstones with Cyryllic, Latin, Hebrew, Japanese and Chinese faded inscriptions used as a path stones or large tombstones as benches for open theater seatings or are discarded among the workers housing and ticket booths in Amusement Park. Sic transit gloria mundi of then European town, on that bones Chinese Harbin was built.

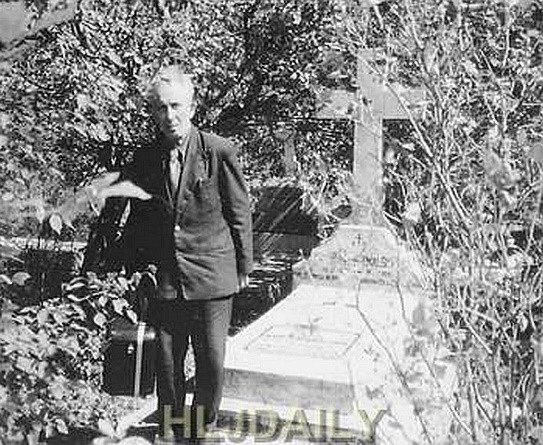

Some commemoration of foreigners deceased in Harbin is in the part of Huangshan municipal cemetery with small synagogue and memorial with the David’s star beside the small Orthodox chapel. There are buried remains of some hundreds of Jews and Russians or rather mostly empty graves with only headstones and crosses removed from old graveyards. There are about 16 Polish crosses and tombstones scattered around with two graves of Stokalski family. Engineer Edward Stokalski, the last Pole that left Harbin in 1993, had made small concrete memorial cross with inscription „Symbolic grave for all the Poles buried from 1898 to 1984 in Harbin desolated cemeteries”.

Przypisy:

Archiwum Towarzystwa Chrystusowego dla Polonii Zagranicznej, Poznan, Harbin Catholic Parishes Death Register Book, inv.no : DR XIV.7.1 – DR XIV.7.5

- Andreeva&N.A.Gavrilova, Frantisek Vinkler-khudozhnik monumentalist. Sled v istorii Vladivostoka, in : Gumanitarnyie issledovaniia v Vostochnoi Sibiri i na Dalnem Vostoke, 2 (2013), p. 15-21

Associated Press News, August 6th 1985 (interview with E. Stokalski)

- Bakesova, Legionari v roli diplomatu. Ceskoslovensko-cinske vztahy 1918-1949, Prague 2013

- Bakich, List of burials at Pokrovskii („old”) cemetery (provided kindly for the author)

- Ben-Canaan, A Continuing Quest for a Peaceful Resting Place in Harbin : The Relocating Process of the Harbin Jewish Cemetery to Huangshan in : Mizrekh Vol. 2, 2010, p. 1-18

Chiny w oczach Polakow. Ksiega jubileuszowa z okazji 60-lecia nawiazania stosunków dyplomatycznych miedzy Polska a Chinska Republika Ludowa, ed. J.Wlodarski, K. Zeidler and M. Burdelski, Gdansk 2010

Fr. G. Kolodziejczyk letter to the author, dated 1th August 1985 from Virginia (Australia)

Daleki Wschód (Polish bimonthly), Harbin 1932-1936

- Goncharenko, Ruskii Harbin, Moscow 2009

- Grochowski, Polacy na Dalekim Wschodzie, Harbin 1928

- Grochowski, Polacy w obronie Hongkongu in : Kontrasty, 5 (226) 1988, p. 20-23

- Hosek, A Good Pitch for Busking : Czech Compatriots in Manchuria 1899-1918, in : Journal of the Center for Northern Humanities, 3 (2010) p.15-28

Entangled Histories. Transcultural Past of Northeast China, ed. D. Ben-Canaan, F. Gruener & I. Prodoehl, Heidelberg 2014

- Levoshko, Zhurnal „Arkhitektura i Zhizn” v arkhitekturnoi istoriografii russkogo Harbina in : Istoriia i Kultura Vostoka Azii: Materialy Mezhdunarodnoi Nauchnoi Konferentsii . Novosibirsk 9-11 Dekabria 2002, Novosibirsk 2001, p. 128-133

List of deceased Catholics in Harbin and Manchuria 1907-1957 compiled by Author

- Majdowski, Kosciol Katolicki w Cesarstwie Rosyjskim : Syberia, Daleki Wschod, Azja Srodkowa, Warsaw 2001

- Martin, C’est de Chine que je t’écus … : Jules Leurquin, consul de France dans l’Empire du Millieu au temps des troubles , Paris 2004

- Meyer, Life and Death in the Garden. Sex, Drugs, Cops, and Robbers in Wartime China, Lanham 2014

Memory and the Impact of the Political Transformation in Public Space, ed. D. Walkowitz and L. Knauer, Durham 2004

- Nilus, Istoricheskii obzor Kitaiskoi Vostochnoi zheleznoi dorogi. V. 1. 1896–1923, Harbin 1923

J.M.Planchet, Les Missions de Chine et du Japon, Beijing (ed. 1916 – 1931)

Les Mission de Chine, Beijing (ed.1936-1940/41)

Russkii Harbin : Opyt zhiznestroitelstva v Usloviiakh Dalnevostochnogo Frontira, ed. A&A Zabiiako, A. Levoshko, S. Khisamutdinov, Blagoveshchensk 2015

- Symonolewicz, Miraze Mandzurskie, Warsaw 1932

- Tairov, O kladbishchakh v Harbinie, in : Politekhnik, 11 (1984) Sydney, p. 52-53

Tygodnik Polski (Polish weekly ), Harbin 1922-1941

Velikaia Man’chzhurskaia Imperiia. K desatiletnemu iubileiu, ed. M. Gordeev and R. Kato, Harbin 1942

Plans of Harbin :

-Chinese version of Russian urban planning of Harbin 1900

-Russian plan of Greater Harbin 1933 (part with details of Russian&UCSC cemeteries)

-Chinese plan of Harbin 1946 (cemeteries in greater Harbin)

PHOTOGRAPHS AND MAPS CREDITS

Archiwum Akt Nowych, Warsaw, Kolonia Polska w Mandzurii [1914] 1917 – 1949 [1951] (fotografie), coll. No.: Pl/2/Pl-2- 198/0 – Photo c.

- Bakesova – Photo u.

- Grochowski, Polacy na Dalekim Wschodzie, Harbin 1928 – Photo l.

- Goncharenko, Russkii Harbin, Moscow 2009 – Photo y.

Google Earth maps – Illustration z.

Hsinhua News Agency – Photo zi.

Library of Congress, Washington – Illustration f.

Ksiaznica Pomorska, Szczecin – Photos d, e, j, k, m, n, p.

Boris Martin – Photo t.

- Nilus, Istoricheskii obzor Kitaiskoi Vostochnoi zheleznoi dorogi. V. 1. 1896–1923, Harbin 1923 – Photos h, i.

http://forum.vgd.ru/post/614/31743/p2055502.htm – internet website – Photo s.

Tygodnik Ilustrowany, 45(1905) Warsaw – Photo w.

Authors’s collection of family photos, illustrations and maps – Photos and illustrations g, o, r, x, y, zii.

Jerzy Czajewski Civil engineer by profession, freelance writer of articles on Polish historical cartography and fortifications of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Z Dziejów Kartografii T. XIV; Polski Przegląd Kartograficzny; Inżynier Budownictwa; www.fortifiedplaces.com ), on turbulent time of reign of Polish Vasa dynasty (Pro Memoria; Spotkania z Zabytkami; Focus Historia; Край Смоленский, Kronika Zamkowa. Roczniki) and on history of Polish diaspora in China (extensive foreword to the exhibition’s album Poles in Manchuria 1897-1949, Szczecin 2015; StuDeo Studienwerk Deutsches Leben in Ostasien e.V ; 雑誌『セーヴェル(Север); Foreigners in China Magazine)

czytaj więcej

Voices from Asia – introduction

We would like to cordially invites all to the new series "Voices from Asia" that is devoted to the Asian perspectives on the conflict in Ukraine. In this series, we publish analysis by experts based in Asia or working on Asian affairs who present their positions on this matter.

We would like to inform, that Observer Research Foundation has published article of Patrycja Pendrakowska - the Boym Institute Analyst and President of the Board.

Patrycja PendrakowskaBook review: “Korean Diaspora in Postwar Japan – Geopolitics, Identity and Nation-Building”

Book review of "Korean Diaspora in Postwar Japan - Geopolitics, Identity and Nation-Building", written by Kim Myung-ja and published by I.B Tauris in 2017.

Nicolas LeviLessons for China and Taiwan from the war in Ukraine

The situation of Taiwan and Ukraine is often compared. The logic is simple: a democracy is threatened by a repressive, authoritarian regime making territorial claims and denying it the right to exist.

Paweł BehrendtOnline Course: “Conflict Resolution and Democracy”

The course will be taught via interactive workshops, employing the Adam Institute’s signature “Betzavta – the Adam Institute’s Facilitation Method“, taught by its creator, Dr. Uki Maroshek-Klarman. The award-winning “Betzavta” method is rooted in an empirical approach to civic education, interpersonal communication and conflict resolution.

Not only tests and masks: the history of Polish-Vietnamese mutual helpfulness

On the initiative of the Vietnamese community in Poland and Vietnamese graduates of Polish universities, our country received support from Vietnam - a country that deals with the threat posed by Sars-Cov-2 very effectively.

Grażyna Szymańska-MatusiewiczA Story of Victory? The 30th Anniversary of Kazakh Statehood and Challenges for the Future.

On 25 May 2021, the Boym Institute, in cooperation with the Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, organised an international debate with former Polish President Aleksander Kwaśniewski (1995-2005).

Are Polish Universities Really Victims of a Chinese Influence Campaign?

The Chinese Influence Campaign can allegedly play a dangerous role at certain Central European universities, as stated in the article ‘Countering China’s Influence Campaigns at European Universities’, (...) However, the text does ignore Poland, the country with the largest number of universities and students in the region. And we argue, the situation is much more complex.

Patrycja PendrakowskaGuidance for Workplaces on Preparing for Coronavirus Spread

Due to the spread of coronavirus, the following workplace recommendations have been issued by the Ministry of Development, in cooperation with the Chief Sanitary Inspector. We also invite you to read article about general information and recommendations for entrepreneurs.

Book review: “North Korea’s Cities”

Book review of "North Korea’s Cities", written by Rainer Dormels and published byJimoondang Publishing Company in 2014.

Nicolas LeviSearching for Japan’s Role in the World Amid the Russia-Ukraine War

The G7 Hiroshima Summit concluded on May 21 with a communiqué reiterating continued support for Ukraine in face of Russia’s illegal war of aggression. Although Japan was perceived at the onset of the war as reluctant to go beyond condemning Russia at the expense of its own interests, it has since become one of the leading countries taking action during the war.

Rintaro NishimuraThe link between EU Aid and Good Governance in Central Asia

Nowadays all the CA states continue transitioning into the human-centered model of governance where the comprehensive needs of societies must be satisfied, nevertheless, the achievements are to a greater extent ambiguous.

After the darkness of the Cultural Revolution, the times of the Chinese transformation had come. In 1978, Deng Xiaoping realised the need to educate a new generation of leaders: people proficient in science, management and politics. Generous programmes were created that aimed at attracting back to China fresh graduates of foreign universities, young experts, entrepreneurs and professionals.

Ewelina HoroszkiewiczYoung Indo-Pacific: Forward-looking perspectives on the EU Indo-Pacific Strategy

The Boym Institute, working with other think tanks, organizes panel discussions on topics related to the European Union's Indo-Pacific strategy

Interview with Uki Maroshek-Klarman on “Betzavta” method

Interview with Uki Maroshek-Klarman - Academic Director of the Adam Institute for Democracy and Peace in Israel. Founder of "Betzavta" method, which was created with intention of streghtening people's participation in society and making conflicts easier to solve.

Patrycja PendrakowskaEnvironmental problems transcend not only national borders but also historical periods. And yet debates on the necessary measures and timelines are often constrained by considerations of election cycles (or dynastic successions) in any given country.

Dawid JuraszekAiluna Shamurzaeva – Research Fellow at the Boym Institute

Her research focuses on political economy, migration studies, and international trade. Ailuna, we are more than happy to welcome you to the team!

Polish-Asian Cooperation in the Field of New Technologies – Report

Polish and Polish-founded companies are already on the largest continent in sectors such as: IT, educational technology, finance, marketing, e-commerce and space. Despite this, the potential lying dormant in the domestic innovation sector seems to be underutilized.

The number of confirmed executions and frequent disappearances of politicians remind us that in North Korea the rules of social Darwinism apply. Any attempt to limit Kim Jong-un's power may be considered hostile and ruthless.

Roman HusarskiForeign Direct Investment in Vietnam

Thanks to continuous economic development, Vietnam attracts a record number of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). The catalyst for such a strong growth of FDI in Vietnam is not only the ongoing trade war between the US and China, but also new international agreements.

Jakub KrólczykWomen in Public Debate – A Guide to Organising Inclusive and Meaningful Discussions

On the occasion of International Women's Day, we warmly invite you to read our guide to good practices: "Women in Public Debate – A Guide to Organising Inclusive and Meaningful Discussions."

Ada DyndoDr. Nicolas Levi with a lecture in Seoul

On May 24 Dr. Nicolas Levi gave a lecture on Balcerowicz's plan in the context of North Korea. The speech took place as part of the seminar "Analyzing the Possibility of Reform and its Impact on Human Rights in North Korea". The seminar took place on May 24 at the prestigious Yonsei University in Seoul, South Korea.

WICCI’s India-EU Business Council – a new platform for women in business

Interview with Ada Dyndo, President of WICCI's India-EU Business Council and Principal Consultant of European Business and Technology Centre

Ada DyndoWe would like to inform, that Observer Research Foundation has published article of Patrycja Pendrakowska - the Boym Institute Analyst and President of the Board.

Patrycja Pendrakowska